10 Aug 2022

Jacob de Tusch-Lec examines the ‘old economy’ stocks that are fighting back. Could these old-world stocks be better placed to reward their shareholders as monetary tightening takes hold?

FOR PROFESSIONAL AND/OR QUALIFIED INVESTORS ONLY. NOT FOR USE WITH OR BY PRIVATE INVESTORS. CAPITAL AT RISK. All financial investments involve taking risk which means investors may not get back the amount initially invested.

If you’ve attended one of our presentations or webcasts over the last couple of years, you’ll have heard us explaining why we believe the world is undergoing a process of ‘regime change’ of the type only seen once every few decades. This change is both political and economic. You’ll probably also have seen a version of the table below. In it, we contrast the winners of the decade that followed the global financial crisis with those we think will be the beneficiaries of the next political, economic and financial regime.

|

Then… Post-GFC winners (2009-20) |

Now… Post-pandemic winners (2021-?) |

|

Inequality up |

Wages up |

|

QE |

QT |

|

Disinflation |

Inflation |

|

P/e dispersion increasing |

P/e dispersion narrowing |

|

Corporates |

Voters |

|

Technology |

Capital equipment |

|

Passive |

Active |

|

Growth stocks |

Value stocks |

|

Peace |

War |

|

Globalisation |

De-globalisation / autarky |

|

Intangible assets |

Raw materials |

|

Profitless growth |

Dividend yields |

|

‘Just-in-time’ supply chains |

‘Just-in-case’ inventories |

When we first drew up this table, inflation was not a topic being discussed on the evening news, central banks were more worried about deflation than rising prices and interest rates were being held down rather than pushed up.

In our portfolio, meanwhile, our preference for defence stocks and energy companies over non-dividend-paying software or media companies stood in direct contrast to the majority of global equity funds. Over the preceding decade, many of those funds had become – for rational reasons – increasingly focused on a narrow set of ‘growth’ names in the US. As the p/e multiples being applied to those growth stocks were hitting new highs, the multiples on some of the unfashionable names in our portfolio were moving lower.

‘Old economy’ stalwarts fight back

Source: Bloomberg. As at July 2022.

And now?

Strategically, we believe the direction of travel is clear

Our expectation is that the world described in the left-hand column of our table will continue to give way to the one on the right. That process won’t, however, always be smooth. Markets have a nasty habit of inflicting the maximum degree of pain on the maximum number of people and moments of market or economic stress may cause central banks to hit the panic button. For example, we recently saw a rally in long duration assets as markets believed global central banks had ‘blinked’ and toned down their hawkish rhetoric.

The change we are anticipating, however, is not simply about a short-term shift in monetary policy or in financial markets. Rather, it will be an enduring, multi-faceted process, one that is reconfiguring the global economy to suit politicians and their unhappy voters, rather than multinational corporations and their shareholders. In purely financial terms, it will mean correcting imbalances that built up over almost a decade of what was, at best, skewed investment into technology and ‘last-mile’ delivery services and, at worst, outright malinvestment.

Malinvestment will take years to work its way through the system

To recap one of the central elements of our thesis, a decade of QE and ZIRP (a zero interest rate policy) resulted in today’s social and political tensions and in capital being misallocated on a massive scale. The policies central bankers used to reassure markets in the decade following the financial crisis produced a huge increase in inequality (the asset-owning rich got richer while wage earners didn’t). That is helping to fuel much of the populism and nationalism we see unfolding today.

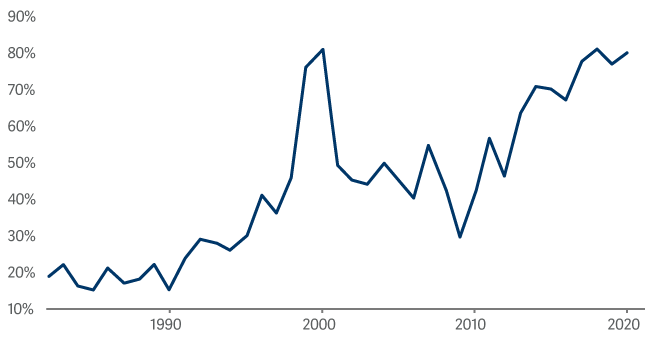

Picturing a decade of malinvestment: Percentage of US IPOs with negative earnings per share

Source: Alpine Macro, 'Macro roadmap for a more turbulent world ahead'. As at 30 November 2021.

QE also resulted in malinvestment. By reducing the time value of money to zero, QE and NZIRP stretched investors’ time horizons. The beneficiaries included:

In many cases, these companies had minimal tangible assets and their shareholders were funding eyewatering operating losses.

There was a long period of underinvestment in the ‘physical economy’…

A side effect of the flood of capital being directed towards profitless growth stocks was that – in relative terms – the cost of capital for established, profitable companies in a range of ‘old-fashioned’ industries increased. The result was that, for almost a decade, we saw underinvestment in some of those companies who keep the physical economy ticking over:

In the case of the energy companies, the market was, in effect, dissuading them from investing in new oil fields, building new refineries or committing the capital needed to maintain and replace productive assets as they matured and degraded. Instead, it was signalling a preference for providing city dwellers with subsidised food deliveries.

CapEx in the energy sector in recent years has barely covered deprecation, allowing for little spending on new discoveries. The consequences of a long period of underinvestment by energy companies are being felt today.

The old economy bites back: refining

The refinery sector is an unglamorous, dirty, ‘old economy’ industry whose products are nonetheless essential to modern life. Designing and assembling the byzantine riddle of pipes, tanks and distillation columns that comprise a modern refinery is costly and time-consuming. A long period of low oil prices (and the greater attention being paid to ESG scores) made capital markets reluctant to fund new refining capacity: a refinery can cost as much as $10 billion to build and take a decade to complete.

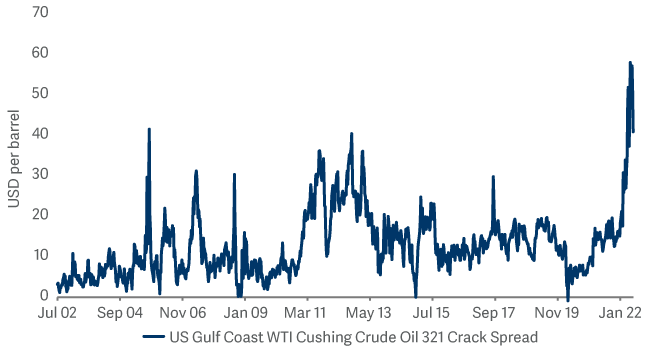

The result is that over the past three years, refining capacity equivalent to around two million barrels of oil a day has been retired in the US – enough petrol to fuel 30 million cars. As demand for petrol, aviation fuel and the host of petrochemicals that refineries produce roared back after the pandemic, the capacity to meet that demand was no longer there. The increase in the ‘crack spread’ – the pricing differential between a barrel of crude oil and the petroleum products refined from it – shows what happens when price-inelastic demand encounters fixed supply. Exxon’s US refineries will generate more profits for their parent company in the second quarter of this year than they did in the previous nine quarters combined.

A lack of refining capacity means the profitability of refiners – the ‘crack spread’ – has increased dramatically

Oil refinery profitability has jumped

Source: Bloomberg, as at July 2022.

It isn’t just refiners…

… as their margins increase, a range of ‘old fashioned’ companies are becoming more profitable. Energy companies led earnings growth in the US market during the second quarter, followed by industrials and materials. Strip out the contribution from energy stocks and earnings growth across the S&P500 would have been negative for the quarter…

In part, this reflects a spike in commodity prices triggered by the invasion of Ukraine. But the improved financial performance of these companies also reflects the leanness of their operating models and the relative strength of their balance sheets. In recent years, while private equity companies were bidding up the value of lossmaking companies one funding round after another, miners and energy companies were paying their down debts and trimming operational fat.

Now, as central banks withdraw liquidity and credit is withdrawn, the tide is turning against companies who need steady infusions of capital merely to survive and back towards mature, profitable companies who are generating profits rather than burning cash.

Resource companies such as Glencore have spent the last five years paying down debt

Glencore - 12m FWD NET DEBT / EBITDA

Source: Refinitiv. As at 3/8/2022

That carries important implications: if the success of your global equity exposure depends on ‘growth’ outperforming in the way it has over much of the last decade, the next few years may prove to be more challenging.

Why we aren’t expecting to ‘buy and hold’

In contrast to the decade in which QE artificially suppressed volatility, its withdrawal seems likely to provoke it. So investors will need to be nimble and be prepared to take short-term tactical positions that may be at odds with long-term direction of travel. The new regime seems unlikely to be a market in which it pays to run your winners – but instead to be active and agile.

In recent weeks, for example, food prices have fallen, metal prices have moved lower and energy prices have eased a little. So was that it for the era-defining shift in financial markets, economics and politics that we have been predicting for so long?

In strategic terms: we don’t think so. Commodity prices may have overshot earlier this year, but the disruption caused by the war in Ukraine was only one trigger for revealing the underlying lack of spare capacity across a range of industries. Almost a decade of underinvestment in some areas – and malinvestment in others – will take years rather than months to correct.

In time, excess profits will attract capital to basic industries, new capacity will come online and super-normal profits will be competed way. But it will take years to build new refineries, to bring new energy fields online, to build new pipelines to connect them and to construct new fertilizer factories. In the meantime, we believe that cashflow-positive companies in the real economy will be able to reward their shareholders more handsomely than lossmaking businesses in the metaverse.

Three ‘old world’ stocks for the new regime

A food producer and processor – Archer Daniels Midland (prospective p/e 12x; forward dividend yield 2.2%)

Over much of the past decade, the global market for foodstuffs seemed almost frictionless when viewed from the perspective of consumers and companies in the West. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the devastating effect of climate change on crops have foregrounded the fragility of food supplies. Even after their recent pullback, food prices are significantly higher than they were a year ago and those increases are being passed on to consumers. (Heinz Tomato Ketchup costs 35% more than it did a year ago…) At times of stress and shortages, ADM’s scale and reach makes it an attractive partner for the world’s biggest restaurant chains and food companies.

A miner – Glencore (prospective p/e 5x; forward dividend yield 10.2%)

We all need to reduce our dependence on burning oil. But the transition to a world in which electric batteries rather than internal combustion engines power our economy will require a huge amount of copper. The IMF estimates that current copper, lithium and platinum supplies are inadequate to satisfy future needs, with a 30% to 40% gap versus demand. So while mining companies are still cyclical businesses, there is now a source of secular demand for copper. During the long period of retrenchment that followed the commodities boom, miners slashed investment and scrapped plans to open new mines and corrected the excesses that once characterised the industry.

A defence business – Rheinmetall (prospective p/e 13x; forward dividend yield 2.6%)

The reason defence stocks appeared (and still appear) so attractive to us should be as obvious as they are regrettable: the world is less peaceful than it was. Defence stocks are beneficiaries of ‘deglobalisation’, heightened geopolitical tensions and the expansion of NATO. The German parliament recently voted to approve a €100bn fund to modernise the country’s armed forces.

To find out more about Artemis visit the website at www.artemisfunds.com.

FOR PROFESSIONAL AND/OR QUALIFIED INVESTORS ONLY. NOT FOR USE WITH OR BY PRIVATE INVESTORS. This is a marketing communication. Refer to the fund prospectus and KIID/KID before making any final investment decisions. CAPITAL AT RISK. All financial investments involve taking risk which means investors may not get back the amount initially invested.

Investment in a fund concerns the acquisition of units/shares in the fund and not in the underlying assets of the fund.

Reference to specific shares or companies should not be taken as advice or a recommendation to invest in them.

For information on sustainability-related aspects of a fund, visit www.artemisfunds.com.

The fund is an authorised unit trust scheme. For further information, visit www.artemisfunds.com/unittrusts.

Third parties (including FTSE and Morningstar) whose data may be included in this document do not accept any liability for errors or omissions. For information, visit www.artemisfunds.com/third-party-data.

Any research and analysis in this communication has been obtained by Artemis for its own use. Although this communication is based on sources of information that Artemis believes to be reliable, no guarantee is given as to its accuracy or completeness.

Any forward-looking statements are based on Artemis’ current expectations and projections and are subject to change without notice.

Issued by Artemis Fund Managers Ltd which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.