01 Feb 2024

Despite progress on female representation in senior financial roles, the industry is nowhere near parity. We explore how finance can create a level playing field for all genders to thrive.

Read this article to understand:

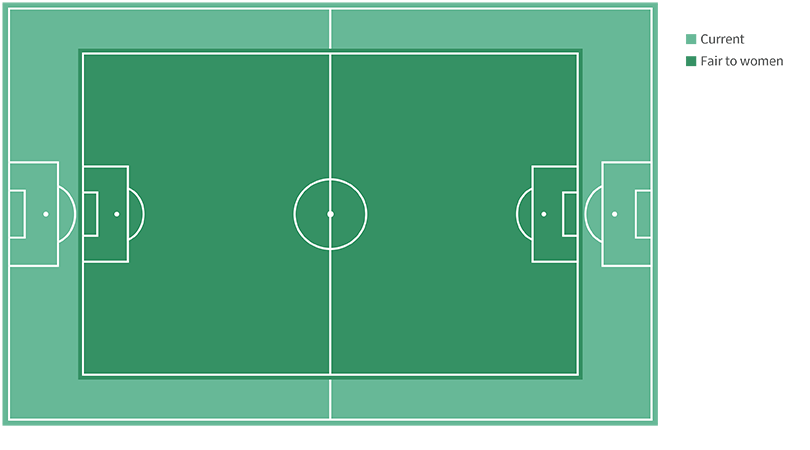

According to a 2019 paper, “most differences between men’s and women’s soccer can be explained by women having to adapt to rules and regulations that are suited for men and their physical attributes. Thus, games are much more demanding for women”.2

Source: Pedersen et al, April 9, 2019.3

But adapting the rules for women is not a given. In rugby, for example, the possibility of switching to a smaller, better-suited ball has not been universally welcomed by female players, as some fear it could damage the reputation of the women’s game.4

There are lessons to be learned for diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) initiatives in other fields, including the investment industry and financial services more broadly. Is it enough to make more space for women where men once dominated? Or should steps towards inclusion also involve adapting structures and institutions? In short, is improving diversity a matter of changing the personnel, or should it also be about reforming the way the game is played?

“I get where [the rugby players] are coming from,” says Kate McClellan, COO at Aviva Investors. “You feel like you've broken through the glass ceiling. The last thing you want is somebody to remind you there was a ceiling.”

She says what changed her view was the wake-up call of the Black Lives Matter movement, which demonstrated that simply “not being racist” was missing the core issue of institutional racism and not talking about it allowed it to fester. Across diversity, including gender, it is crucial to recognise our differences and specific challenges, such as structural barriers to equality.

“For a long part of my career, it has felt like women have been trying to fit into roles to get equality. But that isn't equality,” says McClellan. “We got included, but we didn't necessarily do it on our own terms. I wonder whether part of the problem is women have felt that way for many years, so working in certain roles just isn't attractive enough.”

The diversity agenda is not simply a matter of ethics but also a commercial imperative.

“Clients are increasingly demanding evidence of DE&I practices and culture before they hand over their business,” says Alastair Sewell, liquidity investment strategist and member of the gender workstream at Aviva Investors.

Women also invest less than men on average, so addressing their needs can help improve their savings and retirement outcomes as well as presenting a commercial opportunity.5

But, as in sports, building an inclusive environment is not just about putting the right policies and procedures in place. Instead, it requires an individual commitment from every employee to change the corporate culture.

“We know that diversity within business leads to better decision making and better outcomes for our customers,” says Aviva chief executive officer Amanda Blanc. “While improvements have been made in financial services on gender parity, there is still a lot more we can do.

“It won’t be easy; it needs concerted and sustained effort,” she adds. “Achieving gender parity is up to all of us. We need to stop treating diversity as an initiative, but as a core part of the way we think and work.”

It also requires a significant change in mindsets at every level of companies.

“We have to recognise it can't be just about giving women lots more opportunities they're not really able to take or that leave them feeling conflicted,” says Baroness Helena Morrissey, DBE, chair of the Diversity Project and founder of the 30% Club, among many other roles. “There has to be a rethink of how we live our lives and how work and the rest of life meld together.”

But while the last few years have seen an industry-wide effort to promote DE&I, the pace of change remains too slow. In this article, we explore progress to date, what remains to be achieved and how to create a more level playing field for women and men at work.

Numerous studies have identified correlations between diversity and both business performance6 and fewer adverse business events, such as fraud.7 A diverse workforce means customers are well represented, company reputations are bolstered and better ideas and decisions are made thanks to the consequent diversity of thought.

A broader pool of talent can also be accessed, which is crucial in asset management, an industry largely dependent on human capital.8 This is important from a gender perspective because girls perform better at school on average, whether at GCSE or A-level, and there are more women than men in higher education in the UK today.9,10,11

Yet the industry has a long way to go to achieve a truly gender-diverse workplace.

“The fact much of this talent pool does not find its way into asset management is a huge loss for the industry,” says Jennie Byun, investment director and co-chair of the gender workstream at Aviva Investors.

DE&I is increasingly being considered by companies, either voluntarily or because of regulation. For instance, last year, the European Parliament adopted a law requiring companies to have 40 per cent or more women among non-executive directors or 33 per cent among all directors by 2026.12

“The implication is that DE&I initiatives and progress will increasingly influence business decisions,” says Sewell. “In the investment industry, DE&I considerations routinely appear in new business proposals, meaning better DE&I performers may be more successful in raising assets.”13,14

Multiple initiatives across the industry are promoting, and delivering, real change. A good example is the HM Treasury Women in Finance Charter. The charter was launched in 2016 and encourages financial institutions to commit to improving gender diversity. As of 2021, over 370 firms had signed the charter, covering over 900,000 employees.

“Progress has been made,” says McClellan. “There are more senior women. You only have to look at the top of our tree to see that, and there are examples everywhere else. But they are still only examples: they are not the norm.”

In 2009, Abigail Herron, global head of ESG strategic partnerships at Aviva Investors’ Sustainable Finance Centre for Excellence, was involved in The Observer Good Companies Guide, which that year delved into gender representation in FTSE 250 boardrooms, a blind spot at the time for many companies.

“Fast-forward 14 years; the difference is night and day,” she says. “Companies and policymakers today have seen the work of the 30% Club [a campaign group advocating for greater gender diversity in senior management across business] and empirical evidence that demonstrates diversity of thought is best for company performance. We have seen an uptick in senior female representation in retail and the media, but the financial services sector remains a laggard.”

The recent FTSE Women Leaders Review found women now hold around 40 per cent of board positions in FTSE 100 companies.15 In contrast, according to the HM Treasury Women in Finance Charter Annual Review 2022, UK investment managers averaged 32 per cent female representation in senior management, compared with a financial-sector-wide average of 35 per cent. Both are far from gender parity.16

.png)

Source: HM Treasury Women in Finance Charter, data as of June 2022 and March 2023.17,18

As an example, at the end of 2022, 37.3 per cent of Aviva’s senior leadership (up from 33.7 per cent in 2021), and 42 per cent of the board were women. Having achieved its 2021 target, the group accordingly raised it for 2024.19

Aviva Investors had 31.6 per cent female representation at senior leadership levels at the end of August 2023, up from 25 per cent in 2020. We expect to reach 32 per cent by the end of the year, against a target of 30 per cent.

“Having reached our target ahead of schedule, we will continue to stretch it by increasing the pipeline for senior positions, ensuring transparency and accountability around the promotion and retention of women, reducing unconscious bias and increasing support and awareness,” says Mark Versey, chief executive officer, Aviva Investors.

At a more basic level, financial services firms continue to fail to meet their legal obligations on DE&I. Litigations are routine, as are fines and penalties for failing to deliver on required standards. For example, in May 2023, Goldman Sachs was required to pay $215 million to end a gender bias lawsuit.20

Morrissey adds there are major gaps, particularly in fund management.

“That is critical because that's the lifeblood of the industry and often where the real power base lies,” she says. “The fact we haven't really made any progress in the 35 years since I've been in the industry and are still stuck at about 12 per cent female fund managers is a real problem.”

For instance, Citywire’s 2023 Alpha Female report shows no progress has been made globally in the proportion of female fund managers. Worse still, only 6.2 per cent of new funds launched in 2022 were given to women to run.21 Morrissey believes this is a significant cause of the gender pay gap in the industry. The stubborn lack of progress is the motivation behind the Diversity Project’s Pathway Programme, aimed at helping more women make it into fund management roles (see below). But she adds culture is also an issue, as many women continue to face discrimination and harassment.

.png)

Source: Office for National Statistics, data as of November 11, 2022.22

“It's still microaggressions, sexual harassment; we need to recognise not everybody behaves in a normal, respectful way. There's no point in us having lots of efforts around the pipeline if people are still nervous about the culture of the organisation.”23

In football, the recent World Cup triumph of the Spanish team was overshadowed by Luis Rubiales’ sexually aggressive behaviour during and after the final (forcing a kiss on forward Jenni Hermoso) and the closing of ranks among the higher-ups in the Spanish Football Federation, who initially backed his attempts to stay on in his job. That shows how culture can be a barrier to inclusion and how far we still have to go, despite the good news about growing public interest in women’s football.

Similarly, the CBI and Crispin Odey misconduct allegations show gender discrimination and sexual harassment remain a significant problem in financial services. In their wake, the Diversity Project set up the SafeSpace initiative, offering everyone who works in the industry the opportunity to share experiences of poor behaviour, including bullying, discrimination or harassment. It aims to understand the nature and extent of those behaviours to help address them.24

The UK Parliament also launched a “Sexism in the City” review to assess the barriers women in finance continue to face, with a call for companies and individuals to share evidence.25 As part of its response, the Diversity Project recommended the government should give firms more guidance on the rules around personal conduct.26

Yasmine Chinwala, partner at think-tank New Financial and lead author of the HM Treasury Women in Finance Charter Annual Review 2022, also warns that, not only is progress too slow, it hides a real range between the top and bottom performers in senior female representation.

“The main difference was the starting point,” she says. “On a sectoral basis, the bottom and top quartiles have moved at more or less the same pace. That's a problem because those in the bottom quartile are doing what the pack is doing, but they've done nothing to try and catch up.”

The retail part of financial services – banks and building societies – tend to comprise the top performers, while the institutional side – investment banks and asset managers – are in the bottom quartile.27

Chinwala adds this creates a vicious circle whereby the lack of diversity makes the whole sector unattractive to people from diverse backgrounds, making it harder to improve the sector’s diversity.

“If your sector has become unattractive to women and people from diverse backgrounds, you are going to find it difficult to recruit and retain them, so you can get stuck in a downward loop of losing people or not being able to hire them in the first place,” she says.

Thankfully, something can be done, as shown by initiatives like the HM Treasury Women in Finance Charter and the Diversity Project’s Pathway Programme. The actions companies can take fall into two broad categories: one is ensuring opportunities remain open for women (and men) at every stage of their lives; the other is changing mindsets and company culture.

Herron says a real pinch point is if women choose to have children.

“That is the flashpoint at which the gender pay gap and glass ceiling really kick in,” she says. “How do you nurture that pipeline of female talent? How do you support them at those crunch times when they might need to go part-time because they've got a young family or they’re returning from maternity leave? It's the time when you're going to lose that talent. Those are the key things to focus on.”

Evidence shows women still shoulder the burden of care in families much more than men, meaning they are more affected by things like childcare costs, which forces some people to work part-time to reduce their spending, but also flexible working and promotion opportunities for part-time employees.28

The UK has some of the highest childcare costs in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) group of countries, accounting for a quarter of average household income (Figure 4). For around two-thirds of UK families, these costs exceed mortgage or rent payments and have led 43 per cent of mothers to consider leaving their job.29

.png)

Source: OECD, 2022. Note: Net childcare costs are calculated for couples assuming two children aged 2 and 3, where one parent earns 67% of the average wage and the other earns either minimum wage, 67% or 100% of the average wage. * 2022 for all countries except Israel (2021) and Russia (2018).30

“The Treasury gave with one hand with the Women in Finance Charter and is now taking with the other by trying to make everybody get back in the office,” says Herron. “That is running roughshod over all the benefits of working from home for men and women and the companies they work for. Flexible working means parents can be a lot more involved in their families, if they have them, or in their caring responsibilities. It’s important we don't lose this flexibility.”31

She adds offering longer paternity leave and removing the stigma for men to take it is also important to further gender balance, increase economic output and reduce the gender pay gap and labour-force participation gap.32

“One of the ways we can address it is to make it a better experience to go on parental leave and to come back,” says Herron. “We need to have a much better return-to-work scheme for men and women rather than it being luck of the draw if you have an enlightened and supportive manager. If you can assure parents their return is going to be smooth, it will be beneficial for both, and might induce more men to take paternity leave.”

The key is to ensure there are still opportunities for returning parents, from offering flexible working, returners’ programmes and job sharing to promotion opportunities for part-time employees.

“Is it that if you go part time, you're just treading water, you're overlooked and not given the big projects? How many promotions are there for people who are part-time? Are they just quietly put on the shelf? How do we move beyond pockets of progressive managers to a UK plc-wide culture of supporting parents to retain and grow talent? That's a key conversation to have,” says Herron.

Anum Bandey, controls assurance manager and member of the gender workstream at Aviva Investors, says women returners, job-sharing, term-time contracts and flexible-working opportunities at the company are hugely beneficial.

“We were one of the first investment managers to introduce equal parental leave, we have a sponsorship programme designed for female employees and we have piloted a term-time working policy,” she says.33

McClellan adds offering flexibility can make an employer more attractive, giving the examples of everyone working from home during the pandemic, companies successfully trialling and adopting the four-day workweek and GPs who organise their own time between seeing patients and setting aside a day for paperwork.

“When I work from home and pick up the children from school, I am surrounded by talent and experience with me at the school gate,” she says. “It is shocking that employers can’t find a way to give these women a job so they can still be here at 3:30pm every day. Is that beyond us?”

Chinwala agrees organisations need to challenge outdated perceptions that working part-time or non-standard hours must lead to stagnation. While there has been improvement since the pandemic, it is still a work in progress. “But understanding the nature of the problem is going to be the way to understand how to change it,” she says.

Some firms are building on what Chinwala calls “the laundry list” of basics all companies should be doing to improve this understanding and make changes. The basics entail having diverse shortlists and panels; using inclusive language and offering flexible working opportunities in job adverts; working with external recruiters to target a female audience; introducing regular reporting to monitor progress; and equipping hiring managers with skills and incentives to deliver objectives.34

Key areas for the more advanced initiatives are around accountability, the use of data as an accountability mechanism, and putting in place systems and processes that cannot be subverted.

“Aviva is a good example. When Amanda Blanc took over as CEO, she said it looked like Aviva was going to miss its target but wanted to make sure the firm had done everything possible to try and hit it and find solutions,” says Chinwala.

“When the HR team looked further into it, they realised there were biases within the system,” she adds. “For example, people were far more likely to be able to move into a senior role if they worked in London. And they were able to look at the data and see they had fewer women in London, so they were already on the back foot. Having identified those biases, they could update the process to remove them. If anybody wants to bypass this process, they must get permission from the head of HR or Amanda herself.”

She says companies need to understand where potential bias is slipping in, by understanding the criteria required to move up and where they might have a disproportionate impact on women. Management should then question the need for these criteria and, if they are truly needed, they should plan for them in people’s career paths or find other ways for women to acquire the necessary skills.

Chinwala adds an important point is using data to expose bias, drive accountability and ensure that, when push comes to shove, people continue to follow the process and don’t revert to hiring like-for-like.

Another key element is targeted initiatives in areas where problems are most persistent or female representation is lowest.

As an example, Byun says a key achievement of Aviva Investors’ gender workstream was the launch of a women’s network. “The workstream’s survey of the women’s network identified issues faced by women at Aviva Investors and allowed us to make evidence-based recommendations to our executive team for further change,” she says. “A good example is the identification of root problems in retaining women.”

But she adds the problem isn’t just for women to fix. “The allyship programme is another key initiative we’ve launched through the workstream,” she says.

The Diversity Project’s Pathway Programme, which aims to facilitate women’s progression into fund management roles, can also make a big difference.35

“We have to tackle every stage of the journey. But what I've seen is that, even if women join the industry, too few make it through to fund management roles,” says Morrissey. “This programme is very targeted. We want to create more female fund managers.”

The one-year programme is designed to complement CFA and on-the-job training, brought to the industry by the industry.

“Most people who worked on the curriculum and most of the teachers are fund managers past or present; they know what it takes,” says Morrissey. “Often, it’s about closing small behavioural or technical gaps, such as confidence when presenting to a team of men or understanding cryptocurrency.”

The launch of the programme also helped debunk a few myths. Some companies did not expect to get enough interest from their female employees to fill the two places they could have on the programme and instead had ten times as many applicants. This showed many women had ambitions to become a fund manager the companies were unaware of.

On the flipside, many women had never put themselves forward through lack of confidence and thought they had to be an analyst for 20 years to become a fund manager.

This allowed the 2023 programme to welcome 60 women from 33 companies, and three of the women had already been appointed fund manager seven months in. The programme also expects 80 participants in 2024, from about a third more firms than in 2023.

“It's early days. I don't want to claim we’ve found the solution, but for the first time in my career, I'm confident we're onto something,” says Morrissey.

For all the great programmes and policies, trying to achieve gender balance without the right culture and management is like sailing a ship against the tides. Culture is the critical component with which DE&I can really gain momentum. And while companies are responsible for the policies and programmes, culture stands with each individual.

“Driving diversity and inclusion is essential to running a successful business,” says Chinwala. “It is every manager's job to make sure they are bringing out the best in their team. That is just good management.”

She says making adjustments for a colleague with a disability or allowing flexible working where needed is not about the team member being a woman or having a disability; it is about doing everything possible to run an effective team in a way that brings the best out of each member.

“That doesn't mean changing the team members into clones,” adds Chinwala. “It means helping to bring that team together so they can all make a useful contribution in their different ways.”

Morrissey adds allyship is fundamental because men’s involvement can shift people from thinking it is a women’s issue to understanding it is a business one.

“If men say this is important for the future of our business, for our relationships with our customers, and important to attracting future talent, that's much more valuable,” she says. “Men can champion change, but they have to be authentic about it.”

To promote diversity in their day-to-day roles, there are several things managers and colleagues can do. First, they can be aware of their unconscious biases and work to mitigate them.

“Programmes such as non-inclusive behaviour training can help,” says Bandey. “They educate people on being mindful of language that can be exclusive or offensive and explain how to call out inappropriate behaviour and seek assistance when necessary.”

Managers and colleagues should also encourage and facilitate open discussions and debates that include a range of viewpoints, creating safe spaces for all individuals to be heard.

“Responses from our survey outlined a common theme of women being talked over or ignored in conversations at work,” says Byun. “To counter this, colleagues and managers can actively seek out diverse perspectives and opinions and encourage their colleagues to do the same.”

They can also mentor and support employees from underrepresented groups or engage in reverse mentoring that further aids breaking down unconscious biases and encouraging diverse perspectives.

“Research shows that among college-educated, white-collar professionals, 71 per cent mentored or sponsored protégés that were the same race or gender as themselves,” says Byun.36 “This only propagates the status quo.”

One of Morrissey’s fears is the clamour for people to return to offices, which would be a huge setback.

“Some firms have told me that particularly young men are all back five days a week and the women are not, especially if they’ve got children,” she says. “I worry this is going to create more gender imbalance because people will reward face time and presenteeism.”

This is where Morrissey says senior women like Blanc and senior men can make a difference by giving their full support to flexible working.

“There's lots to consider in terms of making it work, but it is possible; and it is a better, more efficient, smarter way of working. It's not just being nice to people,” she adds. “This is such an opportunity to finally get things right; it is something to try to preserve.”

McClellan says firms need to think more broadly about the design of jobs to attract a wide range of diverse talent, including, but not restricted to, women.

Taking an example of someone who decided not to apply for a fund management role because she was about to start a family and dealing with a sick parent, she argues managing a fund should not be unattainable for people with other responsibilities.

“There isn't any reason why you can't manage money and have a baby or be a carer. But unless we show that, progress will not go as far as it needs to,” she says. “You've got to ask yourself whether the roles are attractive. If they're not, don't change the people, change the roles.”

Morrissey says she still encounters pockets of resistance, from people who think DE&I is a fad, don’t take it seriously or worry about alienating men.

“I don't want to alienate them, but I also don't think we can claim we're done,” she says. “The best way of overcoming that is to get serious, well-respected men who are industry leaders to say this is not a women's issue but everyone's issue.”

It also requires a societal shift that lifts the burden of being the main wage-earner from men’s shoulders and allows them to define their success through other avenues. In Of Boys and Men: Why the modern male is struggling, why it matters, and what to do about it, author Richard V Reeves argues society should drop the expectation of achievement that weighs on men and instead allow them to spread their identity across different areas in the same way women do, including in being a good parent.37

“It’s going to take some undoing, because we are talking about hundreds of years where men were expected to be the main provider,” says McClellan. “Until it's OK for men to leave work at three and pick up their kids from school without worrying about their career prospects or anybody calling them a part-timer, we won't be on a level playing field.”

COVID-19 helped start that shift, as lockdowns showed people who had never worked from home – particularly men – it was possible to be productive and spend time with their family.

“You can have a career and play a significant role in family life; it's not one or the other necessarily,” says Morrisey.

But while one category of men – those at the top – remain dominant and should use their power and privilege to help others, underprivileged men are being overtaken by women at school and work, especially with traditional physically demanding jobs declining. Achieving gender balance and creating a culture of inclusion requires recognising this and helping the men who need it.38

Chinwala believes this is where governments can come in, following the example of Nordic countries, where gender balance did not happen overnight.

“That happened over the past 30-40 years, where there were clear policy interventions focused on ensuring parents of young children weren't the only ones carrying the burden of childcare,” she says. “It's that notion of spreading the load, which not all countries share.”

This is one way asset managers can engage with governments, to explain why it is so difficult to have more women in senior finance roles. Additionally, taking part in initiatives like the Women in Finance Charter or the Women in Finance Climate Action Group39 helps create more standardised data, which asset managers can use to improve their own diversity and challenge the companies they invest in.

“The role of governments and public bodies is to improve our understanding and development of the standardised criteria. We know that when an investor is looking at hundreds or thousands of criteria and data points in its assessment of a company’s viability and success, that will make it easier for them. They can then be part of the accountability mechanism,” says Chinwala.

She is working on a diversity toolkit for investors to provide more standardised and comparable data. One component of this will involve creating a common set of questions for all investors to ask, so companies can produce standardised reporting.

“Having said that, there's also an onus on investors to take DE&I criteria out of the ‘too difficult’ box and find a way to develop their understanding because it is a fundamental part of a well-run business,” says Chinwala. “It hasn't been a priority, but it is something they can actively do; we can see how that was successful for climate change. I think we're on the brink of that with diversity, but it's not established yet.”

Although Morrissey says the industry is limited by its own shortcomings, nothing would ever change if we waited for everyone to be perfect.

“We all have to be part of this effort to complete what we started,” she says. “But as long as we can show we're not just telling other people what to do without doing anything about our own situation, we can use our voting power; otherwise, we're not using the teeth we have.”

For example, Blanc convened the Women in Finance Climate Action Group, a collective of women leaders from business, the public sector and civil society, who collaborate to improve gender equality when designing, delivering and accessing climate finance.40

Herron refers to the Group’s report, Applying a Gender Lens to Climate Investing: An Action Framework, to list what investors should be asking companies on female representation, from the percentage of female employees and new hires to average tenure, the proportion of part-time employees and women who get promoted, the gender pay gap, and policies like parental leave and flexible working, but also policies to prevent gender discrimination.41

“Then there's the whole thread around the percentage of women in senior management,” adds Herron. “How companies support senior and emerging talent as and when they go off on parental leave; how they bring them back in, how they retain and grow them, and what percentage of women are on the board ultimately.”

“The long and short of this discussion is that diversity is not a thing we do,” concludes Chinwala. “It is about trying to understand the people you work with and to help them do their best for the business. It's just being a good manager, but that often gets forgotten.”

THIS IS A MARKETING COMMUNICATION

Except where stated as otherwise, the source of all information is Aviva Investors Global Services Limited (AIGSL). Unless stated otherwise any views and opinions are those of Aviva Investors. They should not be viewed as indicating any guarantee of return from an investment managed by Aviva Investors nor as advice of any nature. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but has not been independently verified by Aviva Investors and is not guaranteed to be accurate. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The value of an investment and any income from it may go down as well as up and the investor may not get back the original amount invested. Nothing in this material, including any references to specific securities, assets classes and financial markets is intended to or should be construed as advice or recommendations of any nature. Some data shown are hypothetical or projected and may not come to pass as stated due to changes in market conditions and are not guarantees of future outcomes. This material is not a recommendation to sell or purchase any investment.

The information contained herein is for general guidance only. It is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this information to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation to any person in any jurisdiction in which such offer or solicitation is not authorised or to any person to whom it would be unlawful to make such offer or solicitation.

In Europe, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Luxembourg S.A. Registered Office: 2 rue du Fort Bourbon, 1st Floor, 1249 Luxembourg. Supervised by Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier. An Aviva company. In the UK, this document is by Aviva Investors Global Services Limited. Registered in England No. 1151805. Registered Office: St Helens, 1 Undershaft, London EC3P 3DQ. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Firm Reference No. 119178. In Switzerland, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Schweiz GmbH.

In Singapore, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Asia Pte. Limited (AIAPL) for distribution to institutional investors only. Please note that AIAPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIAPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIAPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Singapore with registration number 200813519W, holds a valid Capital Markets Services Licence to carry out fund management activities issued under the Securities and Futures Act (Singapore Statute Cap. 289) and Asian Exempt Financial Adviser for the purposes of the Financial Advisers Act (Singapore Statute Cap.110). Registered Office: 1 Raffles Quay, #27-13 South Tower, Singapore 048583.

In Australia, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Pacific Pty Ltd (AIPPL) for distribution to wholesale investors only. Please note that AIPPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIPPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIPPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Australia with Australian Business No. 87 153 200 278 and Australian Company No. 153 200 278, holds an Australian Financial Services License (AFSL 411458) issued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. Business address: Level 27, 101 Collins Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia.

The name “Aviva Investors” as used in this material refers to the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. Each Aviva investors’ affiliate is a subsidiary of Aviva plc, a publicly- traded multi-national financial services company headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Aviva Investors Canada, Inc. (“AIC”) is located in Toronto and is based within the North American region of the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. AIC is registered with the Ontario Securities Commission as a commodity trading manager, exempt market dealer, portfolio manager and investment fund manager. AIC is also registered as an exempt market dealer and portfolio manager in each province of Canada and may also be registered as an investment fund manager in certain other applicable provinces.

Aviva Investors Americas LLC is a federally registered investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Aviva Investors Americas is also a commodity trading advisor (“CTA”) registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) and is a member of the National Futures Association (“NFA”). AIA’s Form ADV Part 2A, which provides background information about the firm and its business practices, is available upon written request to: Compliance Department, 225 West Wacker Drive, Suite 2250, Chicago, IL 60606.