Following unsuccessful attempts in the past, the Japanese government’s structural reforms now seem to be bearing fruit. This has contributed to a record high on the Japanese stock-market, but is it sustainable?

Read this article to understand:

- Why Japanese stocks are surging after a long period in the doldrums

- The impact of corporate governance and market reforms on the outlook for Japanese companies

- What this means for the yen

For Japan watchers, February brought some dispiriting, if familiar, news: the economy is shrinking. Following two consecutive quarters of negative growth, the country is now in what economists call a “technical recession”.

Disappointing GDP numbers are not a new phenomenon in Japan, which has long struggled to rouse itself from an economic malaise characterised by deflation and sluggish growth. But look deeper and there is cause for optimism on the Japanese economy, as structural reforms and long-awaited consumer price rises begin to come through, injecting new life into the stock market. These factors help explain why Japan could offer attractive opportunities for multi-asset investors in 2024 and beyond.

The lost decades

For the origins of Japan’s economic torpor, we need to look back to its boom years in the 1980s, when it became a world leader in sectors such as technology, auto and finance. Between the 1960s and the late 1980s, Japanese economic growth was double that of the US.1 Asset prices surged. Prime real estate in the Japanese capital in 1989 was selling for $20,000 per square foot (almost four times as much as the priciest real estate in the world more than three decades later – even before adjusting for inflation).2

But in 1990, a stock-market crash and a knock-on banking crisis, coupled with structural factors such as a rapidly ageing and shrinking population, led to “lost decades” of slow growth and low inflation, turning into deflation in the 2000s. Interest rates haven’t risen above 0.5 per cent since 1995 and have been negative since 2016.3

Both individuals and companies have focused on saving, in part to make up for the lack of returns on their investments, with the unintended consequence of keeping inflation persistently low. The government and Bank of Japan (BoJ), the central bank, have long tried to break this cycle through policies designed to spark wage and price rises – notably under the “Abenomics” reforms of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – with mixed results.

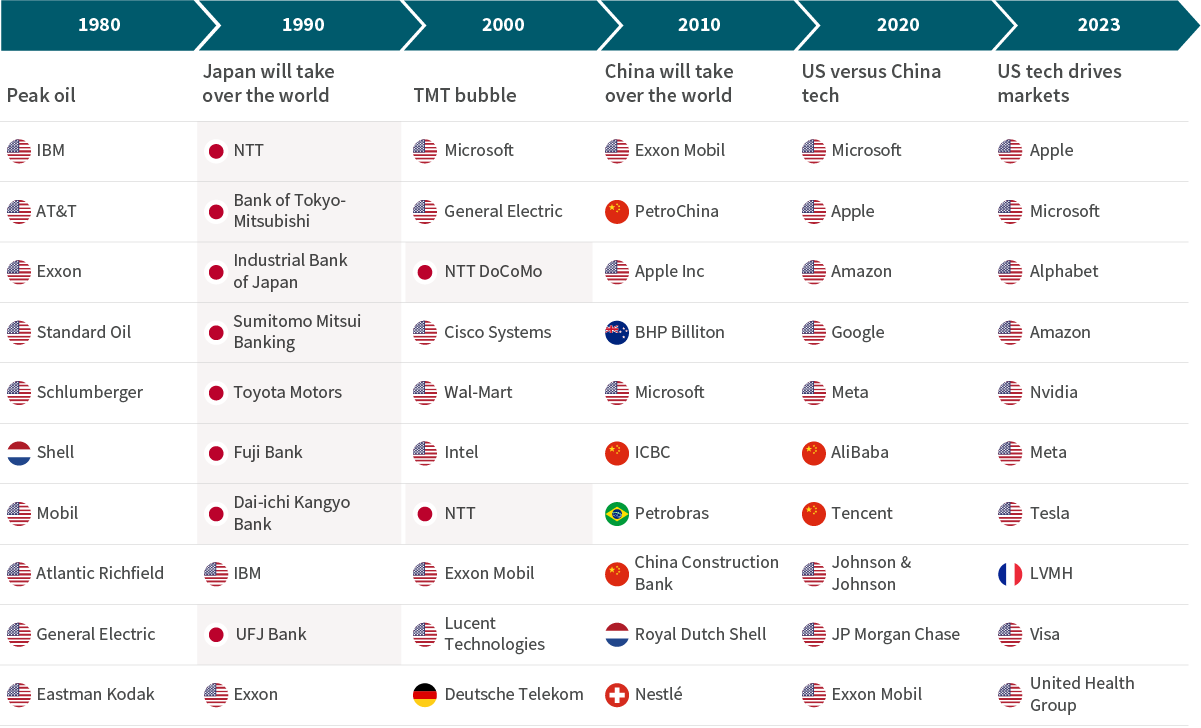

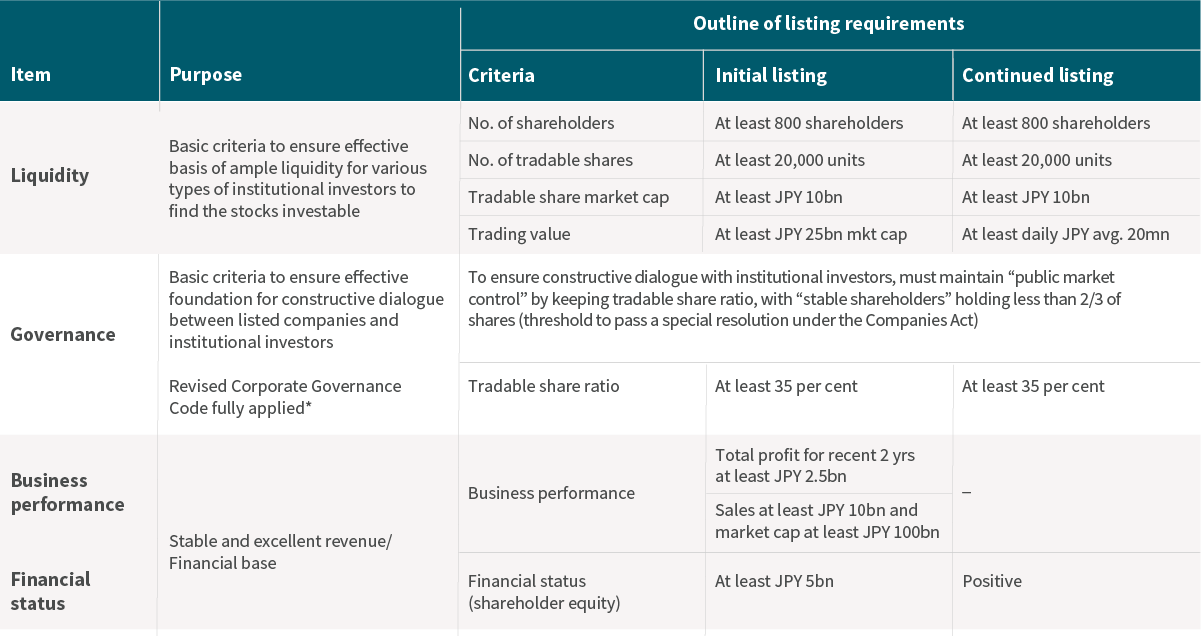

The effects of the lost decades can be seen in Japanese companies’ decline on the world stage. Whereas in 1990, eight of the ten biggest companies in the world by market cap were Japanese, there were only two by 2000, and for the last couple of decades, none have made the list (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ten largest market capitalisations globally, 1980-2023

Note: Berkshire and Aramco have been excluded.

Source: Aviva Investors, February 2024. Data sources: pre-2023 – Macrobond, as of July 31, 2020; 2023 – Statista, as of August 30, 2023.

Rising sums

But now the story looks to be changing. Until recently, investors both domestic and international have not had much incentive to invest in Japanese equities. Yet the country’s economy and stock market have been shocked into better shape over the last two years, and Japanese equities are now at their highest level in 34 years (see Figure 2).

Two key factors have reawakened the sleeping giant that was Japan’s economy: the move from a deflationary to an inflationary environment, and a swathe of crucial governance reforms.

Figure 2: TOPIX index, 1990-2024

.png)

Source: Aviva Investors, Bloomberg. Data as of February 26, 2024.

The result is investors are now finally getting more of a return for the money they are putting in, especially when other initiatives are also encouraging Japanese citizens to invest more of their capital domestically. But while inflation is providing a sugar rush for Japanese stocks, structural reforms will be key to realising their long-term potential.

As with most other major economies, Japan’s inflation rate increased after the world’s emergence from COVID-19 lockdowns and the global supply-chain pressures that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Inflation reached 4.3 per cent in January 2023; it has fallen slightly since then but remained at 2.6 per cent in December – above the BoJ’s two per cent inflation target.4

Overall, the economy is looking healthier too, in spite of the recent quarterly contraction. Taking a longer-term perspective, earnings growth is reasonable. Valuations of world-class Japanese companies are relatively cheap (see Figure 3), so we are looking at earnings for evidence of the positive effects of inflation for companies, particularly on top-line growth and margin expansion. We are looking for increasing costs being passed through to consumers and additional value thus being generated, which should lead to higher corporate earnings and wages. While evidence for this will take time to come through, earnings per share (EPS) and sales growth metrics are positive and overall earnings estimates for Japan are being revised up, which is encouraging.5

Figure 3: Price to book ratio, TOPIX, Euro Stoxx 50, S&P 500

.png)

Source: Aviva Investors, Reuters. Data as of February 26, 2024.

Governance reforms: From sugar rush to healthy living

What gives us confidence these positive trends will be sustained is the fresh momentum on corporate governance reform.

For a long time, Japan’s listed companies operated with little consideration for their shareholders, resulting in poor capital allocation, inefficiency and low margins relative to the rest of the world. In response, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and Financial Services Agency jointly instigated a range of measures to improve the competitiveness and attractiveness of Japanese companies. As part of a broader economic programme to promote growth and address low corporate valuations, Japan is undergoing a multi-year period of corporate governance reform.

The Abe administration published a Stewardship Code in 2014, which it continues to improve. This code puts the onus on institutional investors to push investee companies, through voting and engagement, to run as efficiently as possible. That means a simplification of company structures, more independent directors, clarity around strategy and linking remuneration to performance.

Japan’s Corporate Governance Code was first introduced in 2015, complementing the Stewardship Code by calling on companies themselves to improve their governance standards. In its 2021 update, it emphasised improving board independence and diversity, workforce diversity, executive performance-linked remuneration practices and the consideration of sustainability challenges.

Additional reforms have been enacted to enable shareholders to challenge companies. They include reducing “cross-shareholdings”, reducing barriers to takeovers and reviving an environment for investors to collaboratively engage with firms.

Cross-shareholdings, a longstanding practice whereby companies hold shares in other firms with which they do business, have traditionally insulated management teams from challenges on the part of activist shareholders and locked up capital that might have been productively invested. The drive to reduce them is a key change brought by the corporate governance reforms.

All these measures combined could enable more growth and innovation, promote greater external investment and even encourage more M&A activity. Consolidation could further reduce inefficiencies. For example, there are several large auto manufacturers in Japan, which could arguably be brought down to a smaller number of larger, more-globally competitive firms.

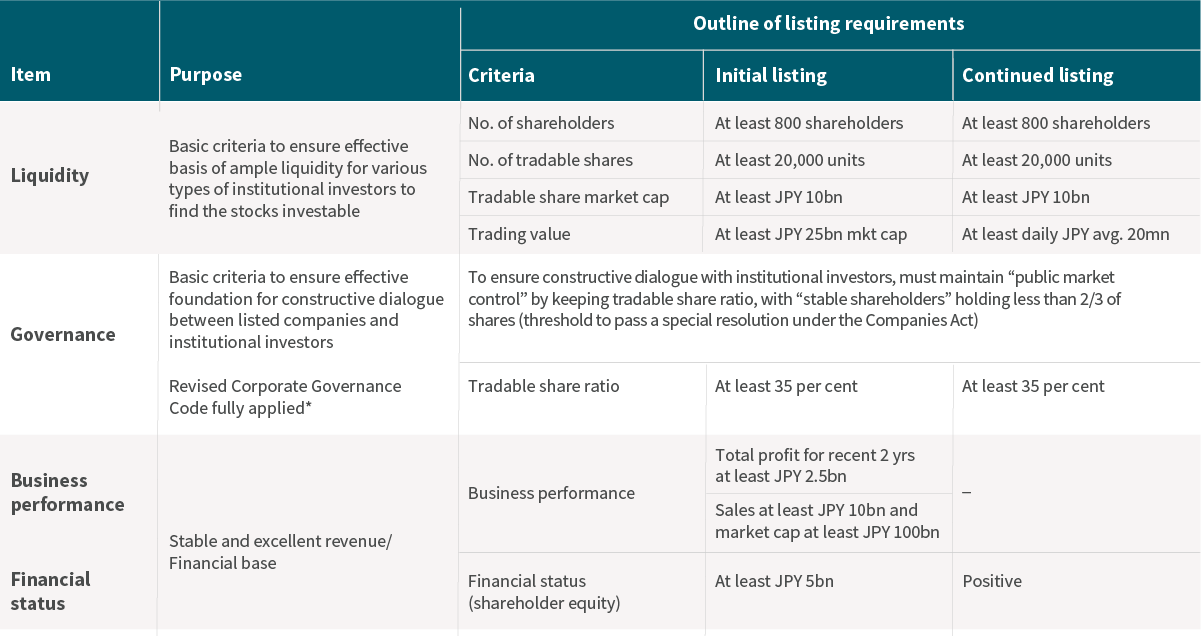

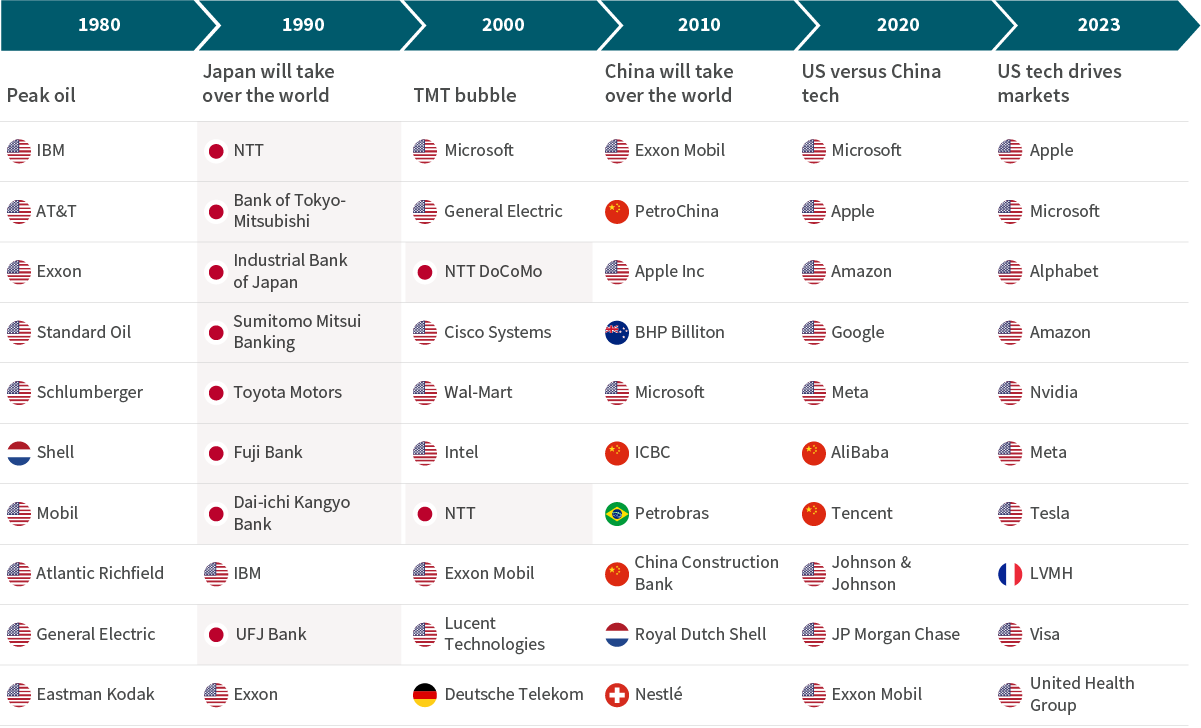

In 2023, the TSE launched a new index called Prime, which favours higher returns on equity and shareholder engagement (see Figure 4). The objective is to create a market that more closely resembles other developed markets, with better management of companies (see Engaging on governance). Japanese listed companies have a strong incentive to be added to the Prime index as a sign of prestige, pushing them to improve. As a result, since the creation of the index, the number of Japanese companies trading below book value has begun to drop. It is work in progress, but early results show there is more value to unlock. Over the long term, this and other reforms should help close Japanese stocks’ valuation gap with the rest of the world (see Figure 3).

Finally, an associated objective of the reforms is to ensure financial assets deliver returns to households, aiming to make the TOPIX equity index more investible for retail customers. Japan’s version of the ISA – called the NISA – has also evolved to encourage more capital flows into equities. The government is aiming to increase the proportion of equities in household assets from its current level of ten per cent to 20 per cent, to bring it in line with Europe and the US, which should support stock prices.

Figure 4: Listing criteria for the Prime market

Note: *Including principles requiring a higher level of governance applied to Prime-listed companies.

Source: Tokyo Stock Exchange. Data as of February 16, 2024.

Investment implications

Historically, there has been an inverse relationship between the TOPIX and the Japanese yen; when the yen has fallen, the TOPIX has done well because a weaker yen helped Japanese exports – and vice-versa. Since the pandemic, the overseas sales ratio for the TOPIX has risen sharply, to over 40 per cent excluding financials, which register sales slightly differently.6

As a result, the currency is garnering interest from the BoJ, which has said it would closely coordinate with the government in monitoring the yen and its impact on the economy. The BoJ hasn’t stated it is targeting a specific currency level, but it wants to ensure exchange rates reflect economic fundamentals and move in a stable manner. As it has intervened in the past, it could well do so again.

As for the future path of base rates, rate rises look to be a case of when, rather than if, in spite of the disappointing quarterly economic data published in February. The BoJ recently said the likelihood of Japan sustainably achieving its two per cent inflation target is gradually rising and that it is increasingly confident conditions for phasing out its stimulus-like yield-curve-control (YCC) policy are falling into place.7 Lower inflation in the service sector was drawing slightly more concern, but the prospect of higher wages is gradually affecting sales prices, feeding through to an increase in service prices – the kind of virtuous cycle Japanese policymakers have long been striving for.

Figure 5: Japan’s perceived inflation outlook, one and three years ahead (per cent)

.png)

Source: Aviva Investors, Business surveys, Bank of Japan, TANKAN Inflation outlook, All Enterprises, All Industries. Data as of January 2024.

If Japanese interest rates rise, the yen could also climb.8 While a moderately stronger yen versus the US dollar could bring challenges for companies, it may not necessarily be a negative for Japanese equities. Japanese companies have expanded their overseas production and shifted to higher-quality exports to avoid competing on price with manufacturers elsewhere in Asia. This has caused both their share prices and earnings to become less sensitive to currency moves. As shown in Figure 6, the correlation between the yen and both earnings per share (EPS) and stock prices has weakened since 2016.

Given the current levels of the yen, we are primarily concerned about the asymmetry. We are therefore overweight both the yen and the TOPIX, supported by inflation and reforms. We are, however, underweight Japanese government bonds, due to our expectations of rate rises and a consequent fall in these bonds’ prices.

Figure 6: TOPIX, TOPIX EPS and USD/JPY exchange rate

.png)

.png)

Source: Aviva Investors, LSEG Datastream. Data as of February 2024.

This isn’t the first time we have seen attempts at structural reforms in Japan, but previous efforts did not gain sufficient momentum to launch a virtuous cycle. This time, however, the reforms are focused on building robustness; but, more importantly, Japan is moving out of deflation. These factors in combination mean reform is likely to be a lot more effective and so far, we have seen a real consensus building, helped by a more engaged TSE.

If inflation is sustained, this will help buoy corporate earnings and be an accelerant for corporate governance reforms which will be key to unlock the country’s long-term value potential.9 They should also encourage investment for growth by Japanese companies, which could help address some of the barriers to broader environmental, social and governance (ESG) challenges such as climate change, by spurring innovation.

Engaging on governance

Good corporate governance isn’t just a “nice to have”; it is material from an investment perspective. Better governance can also unlock opportunities to tackle environmental and social challenges. This is why, as well as welcoming the Japanese government’s policies to improve governance standards such as the infrastructure around ownership rights and encouragement of shareholder activism, we have been engaging with Japanese companies on a number of indicators including remuneration, independence and board diversity.

On pay, the Corporate Governance Code is encouraging companies to link management remuneration to performance. It is encouraging CEOs to take a long-term view by making more of their pay share-based instead of traditional cash-based remuneration.

On diversity and independence, there is currently a push to improve gender diversity in Japan, from board level through to the workforce. The TSE now requires Prime companies to have a third of women on the board by 2030. TSE listing rules also require companies to have at least one-third independent directors on board committees, and at least half on nomination and remuneration committees.

We have been supporting these targets by participating in engagement initiatives to promote more women to boards and senior management positions at Japanese companies, including through collaborative letters to the TSE. We have also been taking action as part of our voting policy. While these measures do not automatically equate to good governance, they are a necessary part of it and provide some measure of initial progress. Thanks to the new TSE rules, we saw a sharp decline in the number of companies we voted against on these issues between 2021 and 2023.

We believe improvement in remuneration, board diversity, and board independence are examples of some measures that can contribute to improved corporate outcomes. However, the success will depend on their application rather than structure and attainment of targets alone. For these changes to be successful, they will need to be complemented by cultural shifts, and this may take time to evolve.

We expect to see continued progress over 2024, with Japan set to issue the next version of its Corporate Governance Code. Those are exciting steps: these measures, combined with the underlying innovative and technological abilities of Japanese companies, could provide new investment opportunities for sustainability-minded investors.10

Japanese companies are also well positioned to help tackle major global challenges like the climate transition, as they have large technological and industrial capacity with strong innovation capabilities. We need to see more of that innovation to help the climate transition journey. Better governance standards and capital freed from cross-shareholdings should foster such innovation to help propel the transition, and it is another area we will be following closely.

References

- World Bank, as of March 4, 2024.

- Historical data from David Pilling, “Bending adversity: Japan and the art of survival”, Penguin, 2014. The most expensive city in the world as of February 2022 was in Hong Kong, where prime real estate was worth $4,530 per sq. ft. See Savills data at: Paul Tostevin and Lucy Palk, “Growth continues apace”, Savills, February 1, 2022.

- IMF, as of March 4, 2024.

- Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, January 18, 2024.

- Tokyo Stock Exchange, IBES, February 26, 2024.

- Goldman Sachs, QUICK, Factset, March 2023.

- “Summary of opinions at the monetary policy meeting on January 22 and 23, 2024”, Bank of Japan, January 31, 2024.

- Future statements are not reliable indicators of future performance or future scenarios.

- Future statements are not reliable indicators of future performance or future scenarios.

- Future statements are not reliable indicators of future performance or future scenarios.

Important information

THIS IS A MARKETING COMMUNICATION

Except where stated as otherwise, the source of all information is Aviva Investors Global Services Limited (AIGSL). Unless stated otherwise any views and opinions are those of Aviva Investors. They should not be viewed as indicating any guarantee of return from an investment managed by Aviva Investors nor as advice of any nature. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but has not been independently verified by Aviva Investors and is not guaranteed to be accurate. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The value of an investment and any income from it may go down as well as up and the investor may not get back the original amount invested. Nothing in this material, including any references to specific securities, assets classes and financial markets is intended to or should be construed as advice or recommendations of any nature. Some data shown are hypothetical or projected and may not come to pass as stated due to changes in market conditions and are not guarantees of future outcomes. This material is not a recommendation to sell or purchase any investment.

The information contained herein is for general guidance only. It is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this information to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation to any person in any jurisdiction in which such offer or solicitation is not authorised or to any person to whom it would be unlawful to make such offer or solicitation.

In Europe, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Luxembourg S.A. Registered Office: 2 rue du Fort Bourbon, 1st Floor, 1249 Luxembourg. Supervised by Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier. An Aviva company. In the UK, this document is by Aviva Investors Global Services Limited. Registered in England No. 1151805. Registered Office: 80 Fenchurch Street, London, EC3M 4AE. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Firm Reference No. 119178. In Switzerland, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Schweiz GmbH.

In Singapore, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Asia Pte. Limited (AIAPL) for distribution to institutional investors only. Please note that AIAPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIAPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIAPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Singapore with registration number 200813519W, holds a valid Capital Markets Services Licence to carry out fund management activities issued under the Securities and Futures Act (Singapore Statute Cap. 289) and Asian Exempt Financial Adviser for the purposes of the Financial Advisers Act (Singapore Statute Cap.110). Registered Office: 138 Market Street, #05-01 CapitaGreen, Singapore 048946.

In Australia, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Pacific Pty Ltd (AIPPL) for distribution to wholesale investors only. Please note that AIPPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIPPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIPPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Australia with Australian Business No. 87 153 200 278 and Australian Company No. 153 200 278, holds an Australian Financial Services License (AFSL 411458) issued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. Business address: Level 27, 101 Collins Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia.

The name “Aviva Investors” as used in this material refers to the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. Each Aviva investors’ affiliate is a subsidiary of Aviva plc, a publicly- traded multi-national financial services company headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Aviva Investors Canada, Inc. (“AIC”) is located in Toronto and is based within the North American region of the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. AIC is registered with the Ontario Securities Commission as a commodity trading manager, exempt market dealer, portfolio manager and investment fund manager. AIC is also registered as an exempt market dealer and portfolio manager in each province of Canada and may also be registered as an investment fund manager in certain other applicable provinces.

Aviva Investors Americas LLC is a federally registered investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Aviva Investors Americas is also a commodity trading advisor (“CTA”) registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) and is a member of the National Futures Association (“NFA”). AIA’s Form ADV Part 2A, which provides background information about the firm and its business practices, is available upon written request to: Compliance Department, 225 West Wacker Drive, Suite 2250, Chicago, IL 60606.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)