Footnotes

05 Mar 2024

By Robin West, Graham Hook

With economic growth stalling and a steady flow of headlines about British companies opting to list in the US, policymakers across the political spectrum are increasingly looking for measures to boost growth and reinvigorate the UK’s public equity markets.

Funding for start-ups and scale-ups, and the attractiveness of the London Stock Exchange as a venue for listing, have received significant policymaker attention. But less attention has been given to what happens to companies after they IPO – to the supply of capital to small and mid-sized listed companies.

Despite a long record of healthy investment returns, structural changes have led to a decline in capital allocations to the UK smaller companies sector. Action is needed to reverse the trend, to ensure that small and mid-sized companies can help drive the economy forward in the future. As the Spring Budget approaches, tax incentives to support the small and mid-cap sector could be the missing part of the plan to provide the equity that smaller listed companies need to invest and grow.

Why do UK smaller companies matter?

Listed smaller companies matter to the UK economy. Their success is more closely aligned to the success of the UK economy as a whole, given they derive a significantly greater share of their earnings in the UK than the FTSE All-Share as a whole. Some 45% of the revenues of the Deutsche Numis Smaller Companies + AIM Index ex Investment Companies (“DNSC+AIM xIC” – which covers the bottom 10% of UK listed companies) derives from the UK, compared to around 23% for the FTSE All-Share Index.

The small cap sector also has more technology businesses than the FTSE All-Share as a whole – 9 % of the DNSC +AIM xIC index versus under 2% of the FTSE All-Share. UK smaller companies are also big UK employers – the sector has nearly double the exposure to the retail and leisure sectors – and it shouldn’t be forgotten that a significant number of today’s FTSE-100 constituents started as small, listed companies that grew supported by capital provided by UK investors.

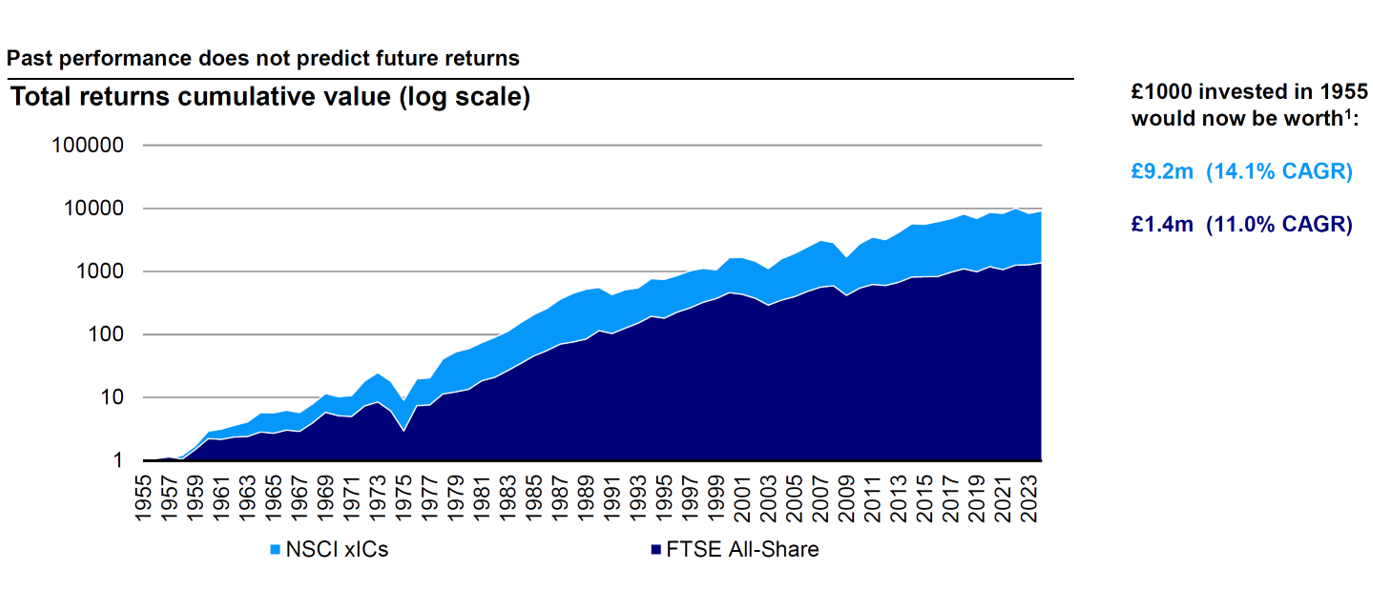

Historically, UK smaller companies have been a dynamic force in the UK economy, producing strong long-term returns for investors. £1000 invested in the DNSCIxIC in 1955 would be worth a massive £9.2 million today, working out at an inflation-busting compound annual return of more than 14% – well above the 11% annual growth record of the FTSE All-Share over the same period.

Figure 1. Total returns for £1000 invested in 1955

Source: Deutsche Numis, 31 December 2023. The indices performance shown is Sterling and is total return. Returns may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations.

Log scale = logarithmic scale, a nonlinear scale used when there is a large range of quantities.

CAGR = Compound Annual Growth Rate.

1This calculation does not include the deduction of charges over the period of investment.

Why are smaller UK companies suffering?

Despite strong performance over decades, in recent years the smaller companies sector has experienced a dearth of new capital, partly due to key structural changes in both the UK economy and the retail and institutional investor landscape.

First, in line with a number of other developed economies, the number of new companies coming to the market to list has declined significantly as companies look to remain private for longer, or for good. Given that most companies looking to IPO are small or mid-cap companies, this has particularly hit the supply of companies to the sector.

Figure 2. Total IPOs

.png)

Source: Deutsche Numis / Scott Evans and Paul Marsh / Invesco

Second, for much of the last decade (apart from post-pandemic recapitalisations), the quantity of funds raised on the UK’s equity markets, for IPOs or for existing listed businesses has been consistently below historic averages.

Figure 3. IPO and follow on fund raising ex Investment Companies

.png)

Source: London Stock Exchange / Invesco

As a result of the fall in IPOs and continued exits through de-listings and takeovers (principally private equity and overseas corporate buyers), the UK has seen a continued reduction in the number of businesses listed on the UK main market.

Figure 4. Number of fully listed UK companies

.png)

Source: Deutsche Numis / Scott Evans and Paul Marsh

Third, retail investors have been withdrawing their money from the UK Smaller Companies sector on a net basis for 16 of the last 20 years.

Figure 5. Net retail sales - UK Smaller Companies

.png)

Source: Investment Association / Invesco (2023 data to Nov’23)

Fourth, institutional investment has also been in decline as defined benefit pension funds – now largely closed to new members – have de-risked and diversified their investment strategies. Allocations have shifted away from equities into fixed income such that, since 2008, the UK equity allocation of UK defined benefit schemes has fallen from 25.8% to 1.4%.

Figure 6. Weighted average allocation of UK defined benefit pension funds

.png)

Source: Pension Protection Fund Purple Book / Invesco

The transition to Direct Contribution (DC) pensions does present an opportunity to attract long-term capital from schemes in accumulation. But the cultural and regulatory focus on cost within DC, rather than value, has increasingly driven trustees to access equities via global indexes rather than active strategies, again to the disadvantage of smaller companies.

The combination of all these factors has created an almost perfect storm for small and mid-sized listed company funding.

Tax incentives work

How, then, should policymakers respond? In the armoury of possible measures, tax incentives can often deliver the greatest success. As the chart below shows for Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) and the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS)1, where investors have been offered tax incentives to support investment in unlisted growth companies, investors have responded by placing significant amounts of capital.

Figure 7. VCT and EIS funds raised

.png)

Source: HMRC / Invesco

With the Spring Budget now just days away, the Chancellor has the opportunity to use tax incentives to boost the supply of fresh capital into the smaller listed companies sector.

What are possible solutions?

One option gaining some traction is the idea of a ‘British ISA’. Placing investment restrictions on the existing ISA allowance would make little sense and would likely prove unpopular. However, an additional, incremental uplift to the allowance for investment in UK small and mid-cap companies – either directly in shares or via investment funds – could be an attractive way to help solve the problem. For example, if just 200,000 ISA investors allocated an additional £5,000 to the UK smaller companies sector, the £1bn of extra funding would represent a sector record for the last 20 years.

Similarly, the Treasury could explore the option of extending the AIM inheritance tax exemption to all smaller listed companies and funds investing in smaller companies. Currently, individuals can take advantage of investing in qualifying AIM stocks that, once held for two years, are exempt from inheritance tax. If the exemption were broadened beyond AIM to fully-listed small and midcap UK companies, it could prove to be an effective way of generating renewed investor interest in the smaller companies sector.

Finally, and while not directly a tax incentive, the Government could look to build on the recent Mansion House Compact with major DC pension providers. By encouraging investment not just in unlisted (private) equity but more broadly in the UK small and mid-cap sector, it would provide better diversification for pension savers as well as the opportunity to support a wider range of British companies with their pension savings.

The missing part of the plan

Building on the support for British start-ups and scale-ups to grow and list on the London Stock Exchange with measures to boost the supply of capital for small and mid-cap listed companies could be the missing part of the policy plan. And it could provide a boost to the overall health of UK public equity markets.

As the example of ARM Holdings plc clearly demonstrates, the UK has an enviable track record of developing innovative growth companies. But support is needed across almost the full spectrum of equity provision to ensure not only that growth companies want to list in the UK; but that once they are listed, they can continue their growth story.

Footnotes

1The EIS offers tax reliefs to individual investors who buy new shares in a qualifying growth company.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

Views and opinions are based on current market conditions and are subject to change.

This is marketing material and not financial advice. It is not intended as a recommendation to buy or sell any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication.