26 Jan 2022

Key Takeaways

We all agree that women should be considered as part of the environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysis of a company. There are very good reasons to do this, the obvious one being that they make up half of the population. When women are considered as an ESG factor, it is often from an operational perspective. Quantitative metrics – such as percentage of women on the board and percentage of women employed – commonly make up the reported ESG metrics for determining how ‘woman friendly’ a company is. Qualitative metrics such as company culture and controversies are also considered.

This is good practice because the way in which a company treats its female employees can often be indicative of the presence of other potentially damaging systemic cultural issues.

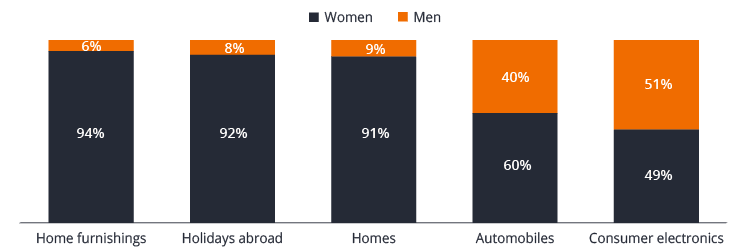

In 2009, Harvard Business noted the growing economic power of women. While this report was produced some time ago, it provides a good baseline and highlights that women determine the majority of household spending decisions (see chart). Another study by Frost & Sullivan highlighted a $4 trillion increase in global female income over two years, while Boston Consulting Group anticipates that by 2028, women will own 75% of the discretionary consumer spend.1,2 Yet, consistently the needs of women are not designed into products and services.

Chart: Women determine the majority of spending decisions

Source: Harvard Business Review, The Female Economy, 2009

When it comes to products specifically designed for women, efforts have at times fallen short. In her book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, Caroline Criado Perez exposes design that fails to accommodate the needs of women, which can, in some instances, be life-threatening.

Dismissive design practices can be dangerous

Criado Perez uses the example of automobiles, a product that should be designed to be gender-neutral. She makes the point that even though men are more likely to be involved in a car crash, women are 47% more likely to be seriously injured and 17% more likely to die. One of the main reasons for this is that car safety is designed from the perspective of the male driver.

I have personal experience of safety not being designed from the female perspective. I used to work on construction sites, where the safety coat, high-visibility vest, safety shoes and gloves were ill fitting because they were designed for men. Often my cumbersome personal protective equipment (PPE) would snag on scaffolding and climbing rigs because it was too baggy, the result of not being provided with PPE that would accommodate a female body. Another female colleague of mine took to wearing multiple pairs of thick socks because they did not make safety boots in her size.

And then I had a moment that changed the way looked at gender from an ESG perspective. I was in an engagement meeting with a company that we were conducting research on. The company had brought samples of the shoes it made, and I asked the CEO and Investor Relations team what I thought would be a simple question “did you bring any of your women’s shoes to look at?”

"The CEO’s face dropped as he and his team had not factored for a woman being present or even for anyone to be interested in seeing the womenswear at all."

I started to reflect on my experiences and the fact that there are so many companies that now understand that products and services should be designed to be inclusive. These companies were taking market share from traditional incumbents. Yet still, how can inclusive design become the norm when it is estimated that 78% of the UK’s design workforce is male?3 I wanted to understand whether my experiences echoed with my female colleagues and I felt the best place to start was athleisure.

Case study: Nike

Nike, one of the world’s largest suppliers of shoes and clothing, has stated its mission to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world. In the past we had shared concerns around the lack of female representation in senior positions within Nike. Since then, the company has increased in Vice Presidents (VPs) that are female and/or are from underrepresented groups. As a result of this diversity, Nike has increased marketing and innovation for women, making sizing more inclusive and creating more storytelling and digital connections through social media. Heidi O’Neill, President of Nike Direct, has been key in promoting investing in women’s wear, fit and design.

We believe that putting talented women in design roles can unleash a wealth of untapped potential, helping to promote alternative thinking and make businesses more cognisant of the needs of women. Without the advocators in leadership and design teams, this voice can easily be lost amid other conversations in design. Company engagement is a fundamental way in which we can hold companies to account while also looking to improve shareholder returns. We believe strongly that as awareness of gender inclusive design increases, companies will need to adapt to avoid being outcompeted by those with a genuine understanding of gender requirements.

Footnotes

1 Frost & Sullivan Global Mega Trends to 2030, March 2020

2 Boston Consulting Group

3 Design Council, Design Economy, 2018

The views presented are as of the date published. They are for information purposes only and should not be used or construed as investment, legal or tax advice or as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector. Nothing in this material shall be deemed to be a direct or indirect provision of investment management services specific to any client requirements. Opinions and examples are meant as an illustration of broader themes, are not an indication of trading intent, are subject to change and may not reflect the views of others in the organization. It is not intended to indicate or imply that any illustration/example mentioned is now or was ever held in any portfolio. No forecasts can be guaranteed and there is no guarantee that the information supplied is complete or timely, nor are there any warranties with regard to the results obtained from its use. Janus Henderson Investors is the source of data unless otherwise indicated, and has reasonable belief to rely on information and data sourced from third parties. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal and fluctuation of value.

Not all products or services are available in all jurisdictions. This material or information contained in it may be restricted by law, and may not be reproduced or referred to without express written permission or used in any jurisdiction or circumstance in which its use would be unlawful. Janus Henderson is not responsible for any unlawful distribution of this material to any third parties, in whole or in part. The contents have not been approved or endorsed by any regulatory agency.

Janus Henderson Investors is the name under which investment products and services are provided by the entities identified in the following jurisdictions: (a) Europe by Janus Capital International Limited (reg no. 3594615), Henderson Global Investors Limited (reg. no. 906355), Henderson Investment Funds Limited (reg. no. 2678531), Henderson Equity Partners Limited (reg. no.2606646), (each registered in England and Wales at 201 Bishopsgate, London EC2M 3AE and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) and Henderson Management S.A. (reg no. B22848 at 2 Rue de Bitbourg, L-1273, Luxembourg and regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier).

Janus Henderson, Janus, Henderson, Knowledge Shared and Knowledge Labs are trademarks of Janus Henderson Group plc or one of its subsidiaries. © Janus Henderson Group plc.