17 Jan 2022

By Tim Drayson

For much of 2021, the Fed focused on the shortfall in employment relative to pre-pandemic levels. This underpinned the central bank’s previous view that the US economy was not close to maximum employment, one of the key criteria for lift-off from zero interest rates. Even today it is still 3-4 million jobs shy.

First, the unemployment rate has continued to plunge. Second, the Fed has become more pessimistic that labour-force participation will pick up sufficiently to prevent unemployment falling further. Third, wage pressures have intensified amid record job openings, quit rates and a chronic shortage of workers. Finally, actual inflation is so far above target that it risks feeding back into wages and higher inflation expectations.

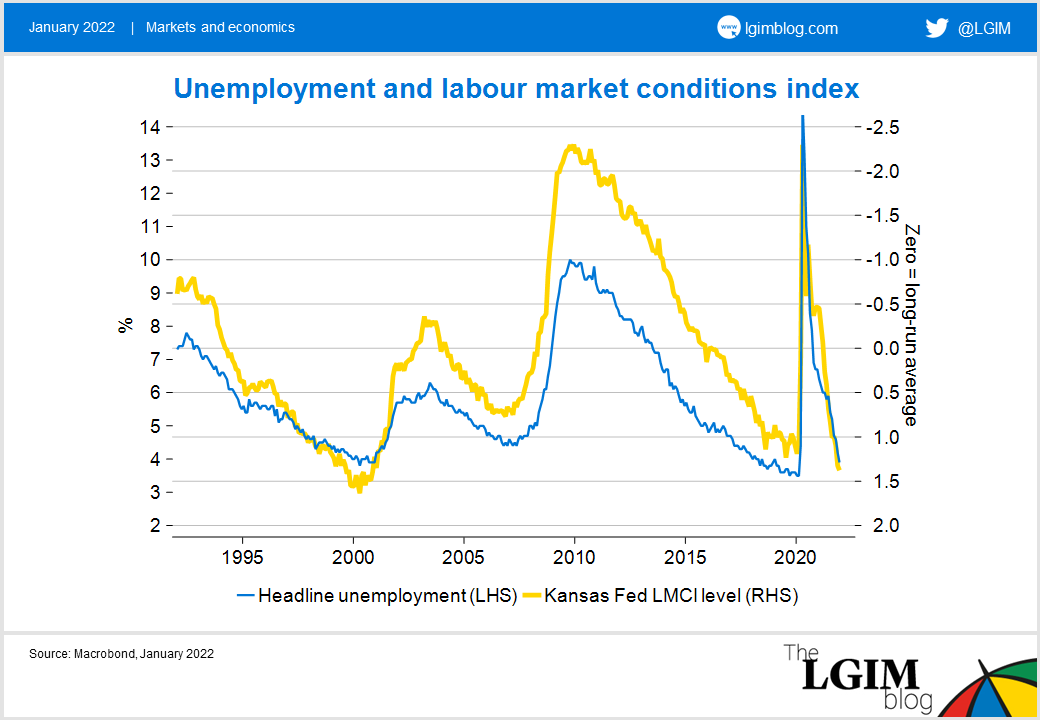

The Fed never defined the precise criteria for maximum employment, but it now looks likely this condition has been met. The central bank’s policymakers look at a range of indicators; the Kansas City Fed labour market conditions indicator contains 24 variables and has returned to cyclical peaks.

But probably the easiest measure to track is the headline unemployment rate. It has fallen a remarkable 200 basis points since June to 3.9% in December. In the last cycle it took almost four years to fall the same amount to the current level. Unemployment is also now below the Fed’s own sustainable long-run estimate at 4.0%. This suggests the US economy could be moving late cycle. Arguably monetary policy should be closer to neutral. Instead, the Fed finds itself a long way behind the curve and still buying assets.

Markets now expect four Fed hikes this year. This seems reasonable even if the pace of hikes may need to quicken in 2023 given our view that the US economy is not especially sensitive to higher interest rates.

The Fed could also move rapidly from today’s tapering of quantitative easing – which is scheduled to end in mid-March – to quantitative tightening, possibly as early as mid-year.

The experience of the previous policy-normalisation episode will help inform the Fed’s choices. There is a strong preference to use interest rates as the primary tool for active monetary policy and to raise interest rates first before adjusting the size of the balance sheet. Balance-sheet shrinking can contribute to monetary tightening, but it is intended to be conducted in a smooth and predicable way.

However, the Fed has identified several important differences from the last cycle. The recovery is stronger, inflation higher and the labour market tighter. The size of the balance sheet is also even bigger, relative to what is ultimately required. This all argues for an earlier start to, and faster pace of, balance-sheet normalisation.

The growth outlook for 2022 remains favourable, in our view, if Omicron burns itself out and some of the supply-chain disruptions ease. The Fed is nevertheless walking a tightrope between returning inflation to target and avoiding a hard landing in the future.

Data sourced from Macrobond, as at 12 January 2022, unless otherwise specified.

Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any Legal & General Investment Management (LGIM) product or service. Views are from a range of LGIM investment professionals and do not necessarily reflect the views of LGIM. For investment professionals only.