26 Sep 2022

Eva Sun-Wai, Fund Manager

As markets, central banks, governments and consumers alike try to adjust to levels of inflation not seen for decades, there is one stream of RPI-linked income that is potentially very attractive to the UK government right now – student loans.

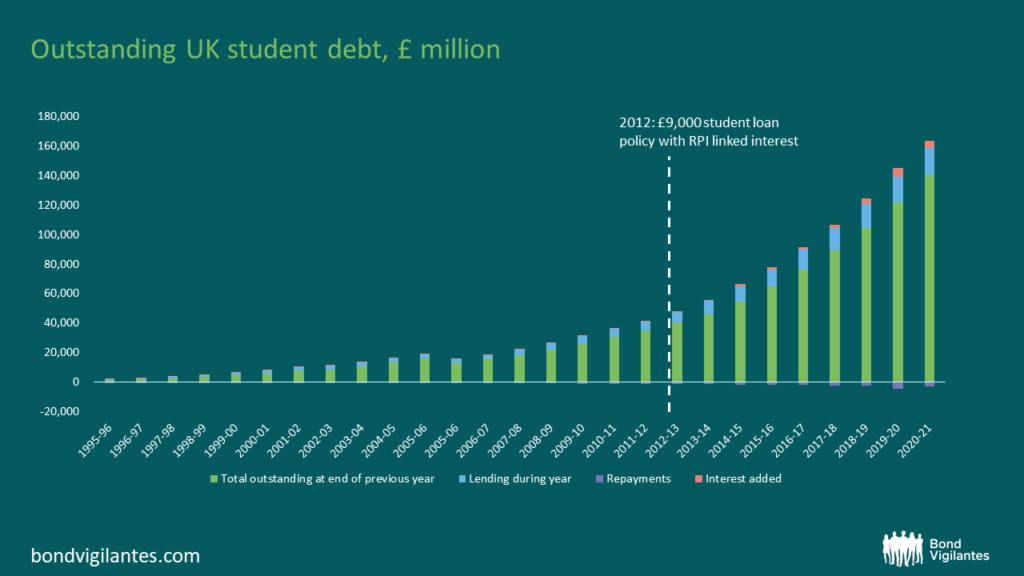

In the UK since 2012, students are likely to have been paying around £9,000 a year to attend university and the vast majority of students rely on student loans (post-2012 loans are known as “plan 2”). This means that outstanding student debt in the UK has grown from around £40 billion to £160 billion in the 10 years from 2011 to 2021.

While many students, graduates and their families will be focused on the immediate costs due to rising inflation, keeping an eye to the future is essential when thinking about debt over the long term. Understandably, many people may not have tracked the true cost of their loans since they started higher education. In actuality, the current structure dictates that their loan has been growing at the rate of the Retail Price Index (“RPI”) + 3% while they have been studying. Once a graduate begins to pay back their loan, the repayments are based on income (9% of salary above the repayment threshold of £27,295), but the loan pot continues to grow at minimum RPI (RPI + 3% for higher earners).

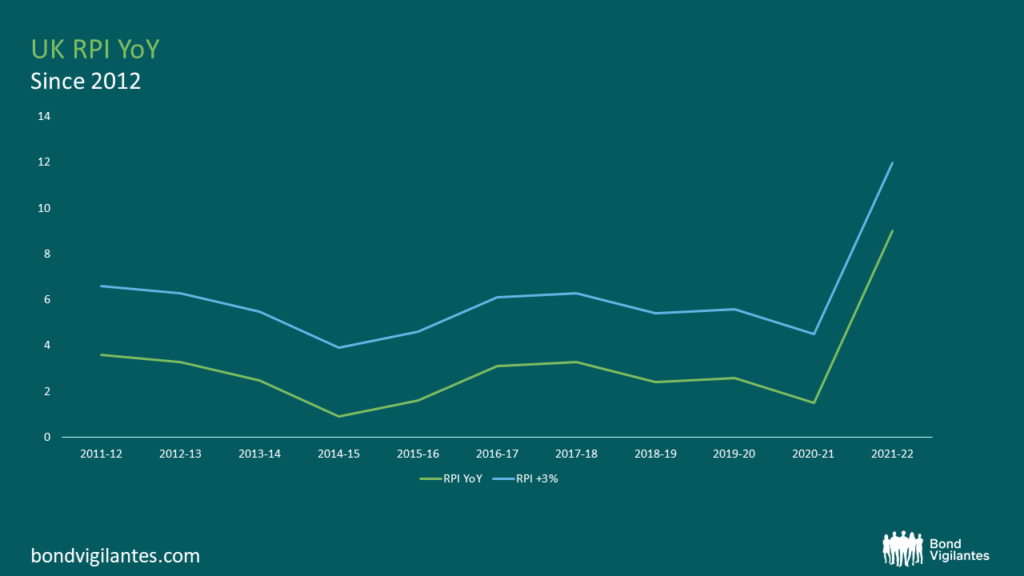

So, why the conundrum? In essence, the March 2021 RPI reading was 1.5%. The March 2022 RPI reading was 9%. So, if a student attends university this September and takes out a loan to do so, it would, in theory, begin growing at a whopping 12% from day one. What’s more, depending on current earnings, graduates with outstanding loans would see their debt grow from somewhere between 9% and 12% for the next 6 months at least.

Let’s break down how post-2012 student loans work.

UK student loans follow a unique structure – on the surface, they almost follow that of an inflation-linked bond. The key difference, is that the ‘coupons’ of a student loan (i.e. the repayments) are fixed, whereas the coupons paid by an index linked bond are linked to inflation. The principal amounts of both are index linked. So, given the coupons & principal amounts of an inflation linked bond are both floating, this keeps the duration of the bond steady. However, by keeping student loan ‘coupons’ fixed and the principal amount index linked, when inflation rises this essentially extends out the duration of the bond, as the principal payment grows faster than the rate at which the fixed coupons are paying it off. Is this a benefit to students, or an unfair structure?

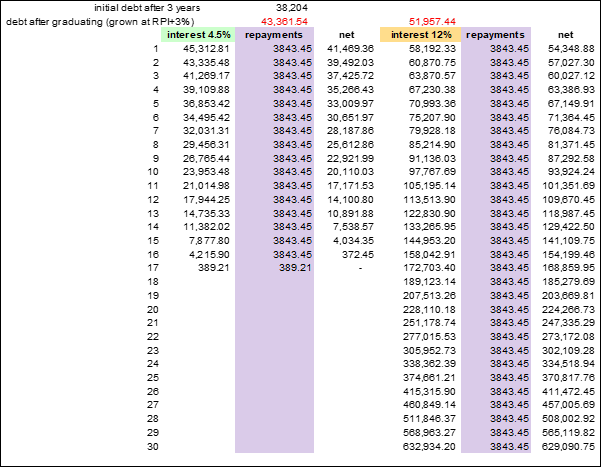

A key structural feature of post-2012 student loans is that any amount not repaid after 30 years is wiped off. The appeal of this, is that for any student who was never going to repay their loan within this time frame, an increase in their debt via higher interest rates, will likely make little difference overall. For higher earners however, their outstanding loan growing at a faster rate than their repayments will make a significant difference, as they will likely be paying off their loan for longer than they would have done at lower rates. To illustrate this, a quick calculation shows that for a high earner who earns £70,000 a year, if RPI perpetually stayed at 1.5% (the March 2021 reading), their pot would be growing at 4.5% per year, and it would take roughly 17 years to pay off their student debt. However, if RPI stayed at 9% indefinitely, their pot would be growing at 12% per year. Such exponential growth vs fixed repayments means that the individual would never come close to paying off their loan. Remember, the monthly repayments are fixed at 9% of one’s salary above the earnings threshold. Whilst not an accurate forecast as inflation prints change continuously (and an individual’s earnings also change over time and potentially move in line with inflation), this shows how the maturity of the loan could materially increase and impact those who would otherwise pay off their loan within the 30 year time frame. It is also worth noting that whilst the average graduate salary is far below this figure, this would affect any individual who has taken out a loan post-2012, so could feasibly affect many people whose salaries have increased over the 10 years since.

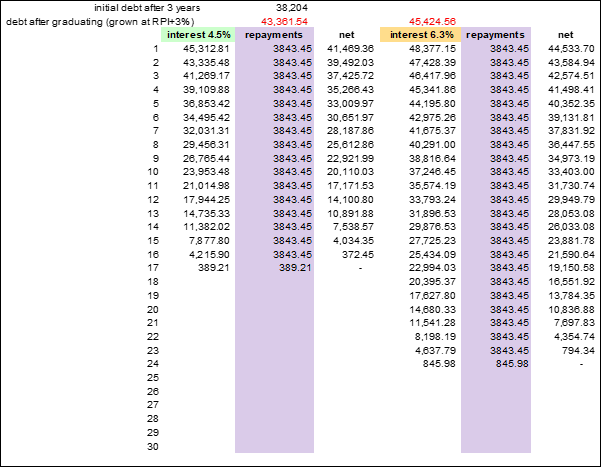

A crucial part of this story, is that the government has noticed this, and has introduced a cap to protect current borrowers from a rise in inflation. They have stepped in to ensure that from September 2022 to end November 2022 borrowers face a maximum interest rate of 6.3% rather than 12%. This makes a huge difference to our rough calculation above, as assuming the maximum interest rate of 6.3% instead of 12%, and keeping everything constant, this individual earning £70,000 per year can still clear their loan within 30 years, albeit it would take an extra 7 years to do so. This also makes a huge difference to prospective students, who can be somewhat reassured that the government is trying to ensure that new graduates will not have to pay back more than they borrow in real terms, assuming salaries move in line with inflation & the repayment threshold also adjusts accordingly.

Why don’t students take out private unsecured loans and pay a lower rate of interest?

6.3% still sounds like a high interest rate when the current UK central bank rate is 1.75%. Why don’t students take out private loans instead that are not linked to inflation? The conundrum here is that like all private loans, this would heavily impact the debt situation of an individual. If a graduate wanted to take out a mortgage for example, a student loan on their personal balance sheet would not impact their credit score (albeit banks do take them into account in terms of affordability). A private loan however, would definitely contribute to one’s credit score and potentially impact their ability to take out an attractive mortgage. A key difference also, is that with a commercial loan, the individual would have to begin repaying the loan regardless of income/personal circumstance to avoid extra fees, but with a government loan one does not have to begin repaying until they earn above the repayment threshold, nor if they are unemployed (and repayments also stop for any borrowers who transition from above the threshold to below it).

Can investors buy student loan asset-backed securities?

The short answer is yes. In general, the securitization of student loans results in liquidity for lenders, greater access for borrowers, and an additional financial instrument for investors. In this light, student loan asset-backed securities seem to be a valuable asset to the economy. The UK government has announced the sale of part of the income contingent student loan book, with the objective of reducing public sector net debt by declassifying loans from their balance sheet. However, this is a relatively small market – especially versus the US, where more of the loans are private and the securitisation market is more developed. In the UK, only around £7.3billion of outstanding student debt is securitised, and only encompasses plan 1 loans (pre-2012). There are tranches that are RPI-linked, but these are small relative to the other tranches and very illiquid. Clearly, the government could do more to shift these loans off of their balance sheet if they wanted to. These initial securitisations were only announced in 2017 and 2018, so perhaps it is a market we will see growing going forward. However, whether this asset class can sustain itself will come down to whether enough borrowers can eventually pay off their debt obligations. Given the repayment threshold in the UK means a large proportion of borrowers are not actually paying, and with the 30 year scrap policy, this could slim down such a prospect and reduce the attractiveness of such an instrument to investors, despite some tranches offering RPI-linked protection.

The key takeaway from all of this, is that whilst headline inflation prints look extremely disadvantageous to UK graduates with outstanding student debt, in reality the government cap on student interest rates will make a huge difference, and provide some reassurance in these turbulent market conditions. It also seems that for now, the government is pretty comfortable having these outstanding loans on its balance sheet, but as the balance continues to grow and the student loan securitisation market becomes more sophisticated, we may see UK student loans emerging as a more accessible asset class for investors.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.