09 Dec 2022

Looking deeper to sort fact from fiction

Joshua Nelson, Head of U.S. Equities

The active versus passive debate is a long and passionate one, with proponents of each camp’s superiority staunch in their conviction. Certainly, the debate is valid, with research1 showing that “average active strategy” returns fail to consistently outperform comparative index returns. Conversely, passive investing comes with inherent shortcomings, not least being the inability to manage risk exposure, particularly in falling or volatile markets. With so much written about the debate over the years, often from a vehement perspective, the waters have become muddied, making it increasingly hard to differentiate between fact and fiction. In this article, we look to provide clarity on some of the common myths and misconceptions surrounding the active versus passive debate.

Passive investing is usually expressed as buying the whole market. For a passive strategy tracking the S&P 500 Index, for example, it would own all 500 stocks in the same weights that they represent in that index. The appeal of a passive approach is that it is low maintenance, achieving returns in line with the index, minus any costs. In theory, you will never beat the market, but neither will you trail by more than the strategy expenses.

However, the gap between theory and practice can be wide. Consider matching the weights of the different securities in the index. This is not an issue when buying in, but what about when prices change the next day? When does rebalancing take place to keep the weights equally matched? What about when dividend payments are made? How is this new money allocated, and when is it invested? There is a lot more happening beneath the surface of passive strategies than most investors understand, which can have a meaningful impact on returns, particularly over longer‑term periods.

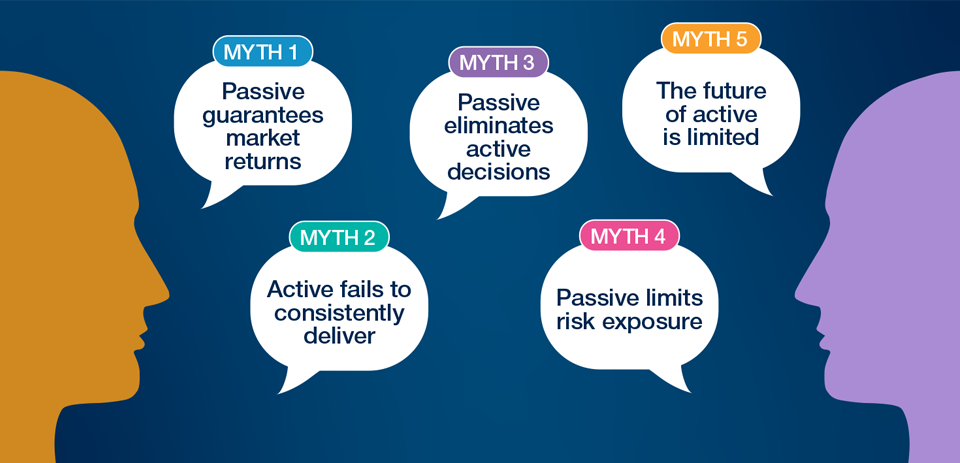

Looking deeper into five common myths

Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

More broadly, passive trading has little impact on market efficiency since it is driven purely by investor flows. In fact, the more assets that are allocated to passive strategies, the more informationally inefficient the markets become. Information‑gathering active strategies, on the other hand, look for, and trade in, stocks that are inefficiently priced. In this way, active management is the essential means by which new, value‑relevant, information is reflected in market prices in a timely way. For markets to remain efficient, and avoid inflated “bubbles” forming, enough funds need to be allocated to active managers.

The generally low‑cost structure of passive investing has obvious appeal. However, investors who choose an investment purely on this basis must understand that, in doing so, they are guaranteed to underperform the index, year in, year out. It is true that many active managers also underperform their comparative indices, and at a higher cost. However, skilled active managers can and do regularly beat comparable passive returns. High‑quality managers that invest significantly in research; follow a disciplined process; integrate environmental, social, and governance considerations; have access to company management; and charge reasonable fees have shown that they can, in fact, consistently capitalize on information inefficiency in the market and benefit from periods of pricing dislocation.

Moreover, with more complex index tracking strategies becoming available, the promise of low‑cost passive investing does not always ring true. Some of the newer exchange-traded fund products that track younger, and less liquid indices, for example, are charging more than some actively managed funds. At the same time, the fees being charged by some active managers have come down considerably over the past decade, in direct response to the significant flow of assets being allocated to low‑cost passive strategies.

Proponents of passive investing point to research suggesting that the average active manager fails to consistently add value after fees. However, the “average active manager” is a broad, and potentially unfair, generalization of the active management industry. Investors should be mindful, for example, of the growing number of so‑called active strategies that are effectively “shadow indexers”—portfolios holding a large number of securities with low tracking error and minimal trading activity, despite charging higher fees. However, despite periodic headlines declaring the demise of active management, there are many active managers that possess the skill and rigor to outperform the market on a consistent basis.

The operative word here is “skill.” To capture the extra return potential that active management attempts to deliver, it is important to select a skilled active manager with extensive research capabilities and a proven track record of outperformance over time. Of course, past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. In addition to a manager’s track record, investors should seek to understand an active manager’s investment philosophy and process and the resources dedicated to uncovering companies with the potential to outperform.

The low‑maintenance nature of passive investing is another key attraction of this approach. However, to say that there is no active decision‑making involved is not quite accurate. For example, in order to be considered for the S&P 1500 Composite Index, which comprises the S&P 500 (large-cap), S&P 400 (mid‑cap), and S&P 600 (small-cap) indices, companies are screened for quality. So, right from the start, active quantitative decisions are being made to exclude part of the U.S. equity market.

Then there is the key decision of which index is best to track and what biases and assumptions are baked into that index. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is price weighted, so stocks with a higher price have a larger weight. A USD 100 stock, for example, would have 10x the weight of a stock at USD 10, even if the USD 10 stock were a much larger and more important company. In practice, this method of weighting is rather arbitrary.

The S&P 500, on the other hand, is weighted by market capitalization—the greater the value of the company the greater the weight in the index. This seems more rational, in that more successful companies should be worth more and, thus, represent larger weightings within the index. Tracking a typical market cap‑weighted index, however, introduces a potentially fundamental flaw—namely, market cap indexes are inherently tilted toward securities that have performed well lately and underweight those that have underperformed. This tends to contradict one of the most basic tenets of investing: buy low and sell high. Meanwhile, market cap indexes are inherently biased toward growth stocks, meaning passive investors are exposed to this growth bias whether they like it or not.

Other forms of the S&P 500 Index weight the stocks differently, such as using equal weights. Compared with the market cap‑weighted index, this index is more exposed to smaller and less valuable companies, and thus introduces a clear value tilt to a passive investment exposure. When you dig into the details, passive investing always involves a degree of active decision‑making.

Passive investors point to the fact that, unlike active management, there is no risk of significant market underperformance. By tracking an index, one’s risk is immediately limited to that of the respective index (minus fees). However, this only considers risk from a narrow perspective and fails to acknowledge the risk mitigation flexibility available to active managers. Take, for example, a highly uncertain market environment, where appealing investment opportunities are few and far between. In this scenario, when consistent with the strategy mandate, an active manager can elect not to invest in the market and simply allocate money to cash instead.

Similarly, active managers do not have to stay fully invested in all market areas. If a certain sector is clearly underperforming or, conversely, appears to be significantly overvalued, active investors can limit their potential risk by underweighting or avoiding these areas altogether. In comparison, passive investors have no option but to remain fully invested across the entire market. Rather than passive investing limiting potential risk, it is arguable that the opposite is true. With an active strategy, the manager has full control over the level of risk exposure and at exactly which point to move underweight or exit an investment altogether, no matter what. This ability means the potential risk is defined, unlike passive investing where potential risk is undefined.

Passive investment flows have grown substantially in recent decades, and assets under management have now surpassed that of active managers. Proponents of passive investing see this transition away from active as a clear and unstoppable trend, some even suggesting that the total consumption of active management is inevitable at some point in the future. This is highly unlikely, in our view, for the simple reason that, as passive assets under management grow, the stock market also becomes more informationally inefficient. And the more inefficient the market, the greater the opportunities for skilled, research‑driven, active managers to outperform.

The rise of online trading software, algorithmic trading programs, and day trading is also resulting in shorter investor holding periods and increased volatility. Many investors claiming to be long‑term investors have shorter investment horizons than traditional long‑term investors. Again, this creates more opportunities for disciplined, true long‑term investors who are willing to look beyond any short‑term market noise.

Active managers—as the conduit through which news is reflected in market prices—ultimately provide an essential function that should benefit all investors, both passive and active. But financial markets do not necessarily absorb and respond to new information and expectations quickly. Particularly, in an environment of regime change and high policy uncertainty, such as we are currently experiencing, market efficiency is not instantaneous, but rather a process. This not only creates room for active management to add value, but in identifying inefficiency, active management can play a pivotal role in correcting such market anomalies and pricing distortions and ensuring the efficient and rational allocation of capital.

Another frequently overlooked function of active management is the role that it plays in providing market liquidity, given the ability to make discretionary trades. Passive strategies, in comparison, must adhere to the pro‑rata trades imposed by the parameters of the respective index. There are clear limits to their freedom to provide liquidity without increasing tracking error risk. The discretionary nature of active manager trading means that they have more freedom to pick and choose which stocks to buy and sell, at any time during the day, providing an ongoing flow of liquidity to the market.

The long‑running debate surrounding active versus passive management shows no sign of abating. Suffice to say that there are valid arguments on both side of the debate, but it is important to not simply take these at face value. Many of the arguments that have come to be assumed as lore, in fact fail to hold up under closer scrutiny. While the appeal of inexpensive passive market exposure is understandable, investors should not ignore skilled active managers and their ability to exploit market inefficiencies and mitigate risk.

More broadly, active management is vital to the overall efficiency of financial markets. By conducting fundamental company research and meeting with management teams, active management leads to what is known as “pricing discovery.” Thus, it is because active management exists that passive investors can be comfortable that markets are efficient and reasonably priced. Or, in simpler terms, without active, there can be no passive.

1.SPIVA (S&P Indices Versus Active) Scorecard. S&P Global, as of June 30, 2022.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.