18 Feb 2022

The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) is the world’s most influential central bank—when it makes major policy decisions, the impact is felt across the globe. It was no surprise, then, that the Fed’s recent announcement that it will begin raising interest rates in March prompted such anxiety among investors about the impact on financial markets.

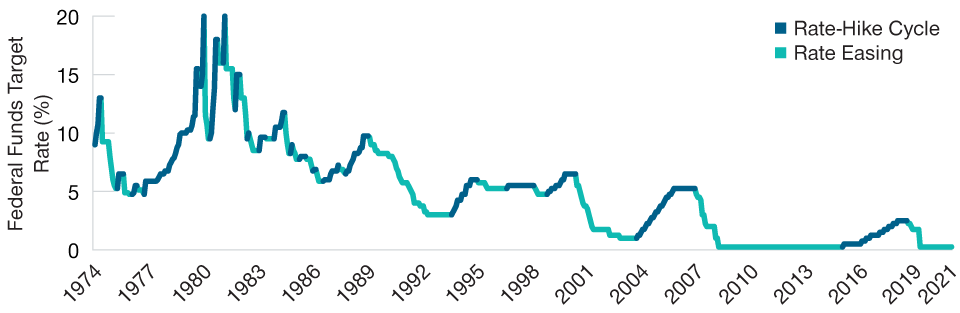

To assess whether this anxiety is justified, we examined the performance of the U.S. stock market, Treasury market, and the U.S. dollar in the 6‑ and 12‑month periods after the beginning of each Fed hiking cycle since 1974. We chose these time periods because we believe they represent the minimum investment horizons investors—rather than speculators or traders—should consider when making tactical investment decisions. The blue line in Figure 1 shows the 21 rate‑hike cycles over the period.

A History of Fed Rate‑Hiking Cycles

(Fig. 1) There have been 21 cycles since 1974

Our findings were as follows:

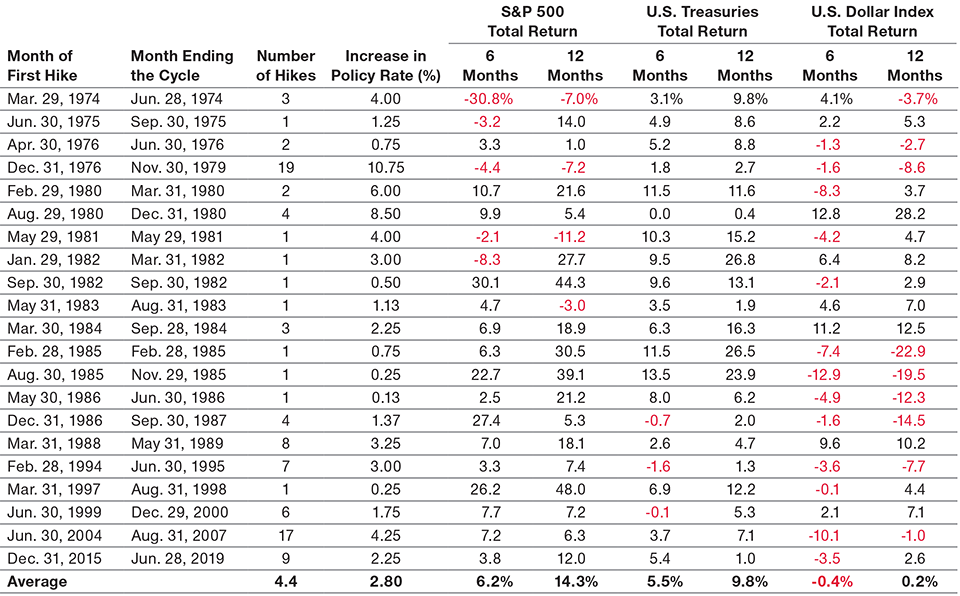

It turns out that for nearly five decades, the U.S. stock market has tended to perform strongly after the Fed has begun a new hiking cycle. Out of the 21 rate‑hike cycles during the period we examined, the U.S. equity market delivered a positive total return 17 times—an 81% hit rate—in the 12 months after the first hike and 16 times—a 76% hit rate—in the six months after the first hike. Since 1984, the hit rate is 100%, with positive total return during all 11 rate‑hike cycles in the six and 12 months after the first increase in policy rates.1

...the U.S. stock market has tended to perform strongly after the Fed has begun a new hiking cycle.Yoram Lustig Head of EMEA Multi‑Asset Solutions

This is somewhat counterintuitive. When rates are raised, financial conditions become tighter, the cost of capital and of borrowing increase, and the discount factor used to calculate the present value of future cash flows rises, leading to lower stock prices (all else being equal). However, interest rate cuts tend to occur during periods when the economy is weak and rate hikes are typically made when business activity enjoys an upward trend and inflation is elevated or rising. The beginning of rate‑hike cycles, then, usually coincides with a relatively strong economy, which in turn is supportive of a buoyant equity market—hence the usual strong performance of stocks in the period immediately following the rate hike.

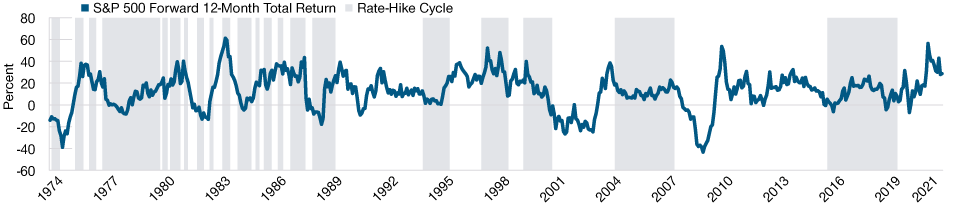

If rate rises continue, however, tighter financial conditions could eventually adversely impact stocks. A visual inspection of Figure 2 shows that rate‑hike cycles tend to start with a strong performance of the stock market over at least the first 12 months—but that performance may turn negative if the cycle is prolonged.

Does this mean we can expect positive stock market performance in the year following the beginning of the next hiking cycle? Here, we must be cautious—context is important. For example, one consideration our analysis does not take account of is the unconventional monetary policy that the Fed has been widely using since the 2008 global financial crisis. Monetary policy levers such as quantitative easing (QE), tapering asset purchase programs and quantitative tightening (QT), forward guidance, and other monetary measures may have taken away some of the impact interest rate changes have on markets or, at a minimum, improved the Fed’s ability to signal forthcoming rate rises to investors.

Stocks Have Performed Well Immediately Following First Hikes¹

(Fig. 2) Performance may turn negative if the cycle is prolonged, however

As of December 31, 2021.

Sources: Federal Funds Target Rate—Upper Bound (U.S. Federal Reserve), S&P 500, analysis by T. Rowe Price. January 1974 through December 2021.

The gray‑shaded areas represent rate‑hike cycles. The blue line is the forward (subsequent)12‑month total return of the S&P 500 Index. Returns are through

December 31, 2021. (see Additional Disclosures).

1 Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Please refer to Appendix: Methodology and Data for additional important

information on our study

Another important factor that our analysis does not include is the impact of Fed policy on investor sentiment. Over the past two decades, central banks have provided a sort of backstop to financial markets, known as the “central bank put.” This was encapsulated in 2012 by then‑European Central Bank President Mario Draghi when he said that the bank would do “whatever it takes” to protect the euro. Those three words became a widely used catchphrase that describes the power of central banks to turn around the fortunes of economies and markets.

Many investors may have been investing in financial markets with reduced fears over the last 20 years because they believed that asset price downturns would be alleviated by central banks. However, if investors believe that the hands of central banks are now tied because of elevated inflation and that the central bank put has effectively been suspended, sentiment could sour.

...long‑term rates may ease when the Fed hikes, supporting the performance of the Treasury market.Michael Walsh Solutions Strategist

The point being: Although the beginning of a Fed rate‑hike cycle does not seem to trigger stock market declines based on past experience, investors need to be mindful of the current context. Other factors, such as the state of the economy, stock market valuations, and investor sentiment, could still cause the stock market to take a turn for the worse.

The U.S. Treasury market tended to deliver positive total returns after the first interest rate hikes in a cycle. Out of the 21 rate‑hike cycles since 1974, the U.S. Treasury market delivered a positive total return 21 times—a 100% hit rate—in the 12 months after the first hike and 18 times— an 86% hit rate—in the six months after the first hike.

This result may be unexpected given the inverse relationship between rate rises and bond prices, but it does make sense. Although short‑term interest rates indeed tend to rise when the Fed is raising its policy rates, longer‑term interest rates mainly reflect three factors: market expectations of future short‑term interest rates, inflation, and economic growth. Because rising policy rates may mean lower inflation levels and slower economic growth in the future, long‑term rates may ease when the Fed hikes, supporting the performance of the Treasury market. Relatively high levels of coupons and yields prevailing for much of the analyzed period also acted as a cushion for Treasury investors.

When comparing the relative performance of the U.S. stock markets with the U.S. Treasury markets in the aftermath of a change in Fed policy, the results are more nuanced. Out of the 21 rate‑hike cycles in our study, the U.S. stock market outperformed the Treasury market 15 times—a 71% hit rate—in the 12 months after the first hike and 11 times—a 51% hit rate—in the six months after the first hike. This further highlights the need to consider all factors and the context of the change in policy and to consider using dynamic asset allocation that can adapt to market conditions as the rate‑hike cycle develops.

Out of the 21 rate‑hike cycles since 1974, the U.S. dollar has appreciated 12 times....Niklas Jeschke Solutions Analyst

The U.S. dollar tended to appreciate against major world currencies over 12‑month periods but depreciate over six‑month periods after a first hike. Out of the 21 rate‑hike cycles since 1974, the U.S. dollar has appreciated 12 times—a 57% hit rate—in the 12 months after the first hike and eight times—a 38% hit rate—in the six months after the first hike.

...investors should consider other ways the Fed influences the economy and investment markets beyond its policy rate....Eva Wu Solutions Analyst

While rising rates may attract foreign investors, boosting the demand for the currency and its value, a number of interrelated factors affect currency movements. Notably, political and economic stability, and the demand for a country’s goods and services, often have a bigger impact on exchange rates than interest rates. Once again, historical currency fluctuations demonstrate that investors should not make decisions solely based on Fed policy but rather consider other potential drivers of the performance of asset classes and currencies.

History tells us that the beginning of a policy rate‑hiking cycle by the Fed does not tend to derail the U.S. stock or bond markets, nor the U.S. dollar. However, while this is good news for investors, it does not amount to a guarantee that those markets will perform well at the beginning of the next Fed hiking cycle. Although Fed rate decisions are very important, investors should consider other ways the Fed influences the economy and investment markets beyond its policy rate, as well as the impact of policy on sentiment and other factors that set the scene for the expected performance of markets.

In our study, we have examined the end‑of‑month federal funds target rate from January 1974 through December 2021. We define a rate‑hike cycle as the time period between the month of the first hike until the month before the first cut. We calculated the total returns of the U.S. equity market (S&P 500 Index), the U.S. Treasury market (Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Index) and the U.S. dollar index (USDX) during the six and 12 months after the month of the first hike in each rate‑hike cycle. Table 1 includes the results.

Table 1: Data

Additional Disclosures