06 May 2022

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the violence that has ensued, has unleashed horror across the world. It has also had an immediate impact on the eurozone economy as soaring commodity prices, financial sanctions, and restrictions on Russian energy exports threaten the post‑pandemic recovery. This will complicate the task of central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB), as they seek to phase out stimulus and gain control over inflation.

There are numerous ways in which the war in Ukraine could affect the European economy. From a geopolitical perspective, the impact will likely be limited: If we estimate the geopolitical “shock” of Russia’s invasion to be somewhere between that of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Korean War, historical precedent suggests it will knock a few points off the eurozone manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). The direct impact on trade could be more significant as sanctions bite: Eurozone exports to Russia had already fallen from 0.9% to 0.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) because of the sanctions imposed in response to the annexation of Crimea in 2014; this will now likely decline to 0.2% to 0.3%.

Since the beginning of the conflict, oil prices have experienced incredible volatility, reaching as much as USD 139 per barrel before falling back again. The U.S. and the UK have banned Russian oil imports, and similar sanctions are being discussed in the EU. While Russian oil will find other buyers, it will take time to reroute deliveries to other countries. This will keep prices elevated for some time.

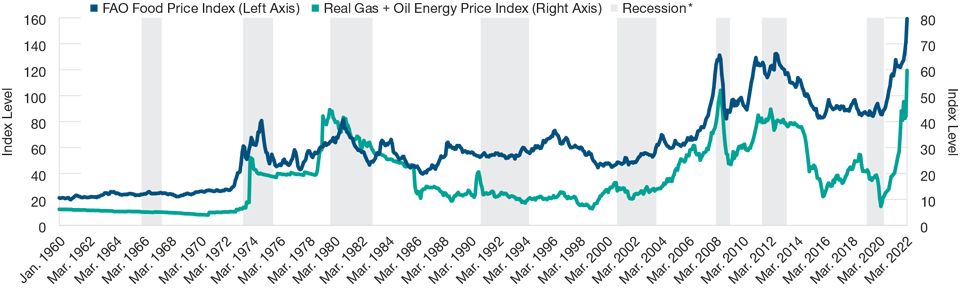

Surges in Food and Energy Prices Have Typically Preceded Recessions

(Fig. 1) Prices have been rising since the start of the war.

January 1, 1960 to March 31, 2022.

January 1, 1960 to March 31, 2022.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

*To determine whether a recession had occurred, we used a series of indicators from the Economic Cycle Research Institute and the Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Sources: World Bank, Food and Agricultural Organisation/Haver Analytics.

Although it is unlikely that the European economy will suffer from a major shortage of oil, energy supply shocks tend to have a persistent negative effect on the real economy. For example, a 20% rise in oil prices, from the prewar level of USD 90 per barrel to USD 108, could lead to an implied reduction of real GDP by around 0.6% and raise consumer price index inflation by approximately 0.9%.1

The rise in gas prices will likely lead to a significant decline in industrial activity...

Rising gas prices will have an even larger impact than oil. Russia supplies 40% of the EU’s gas, with Italy and Germany particularly dependent. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, gas prices in Europe were up by 400% from February 2020; the invasion added a further 50%. European industry relies on gas as an important production input, including for the generation of electricity. The rise in gas prices will likely lead to a significant decline in industrial activity as gas‑intensive production may become too costly relative to imports from other parts of the world, which do not face the same constraints on gas. This 50% rise in gas, if sustained for a month, could temporarily reduce industrial production by 4% to 8%.

Food price increases will also have an impact. The war has already affected food production and distribution in Ukraine, which is a large wheat and grain producer. These food products are usually shipped abroad through ports in the southern part of the country, with the port of Mykolaiv accounting for 50% of all Ukrainian food exports. Because of heavy fighting in Mykolaiv, these products are now shipped via trains to other ports in Europe—a much less efficient way of transporting food. All these costs could significantly add to global food prices over the next six to 12 months.

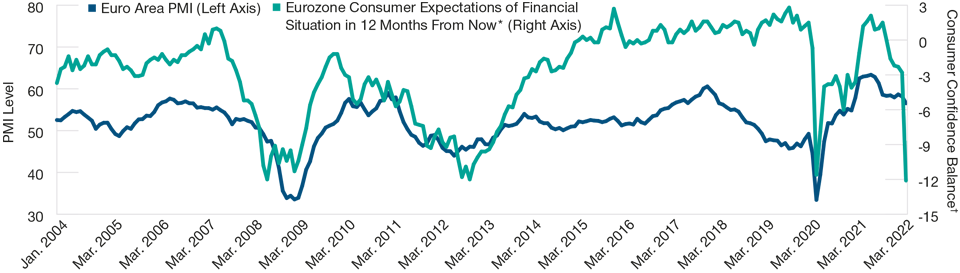

Consumers’ Financial Expectations Have Deteriorated Sharply

(Fig. 2) Manufacturing PMI has traditionally lagged

January 1, 2004 to March 31, 2022.

January 1, 2004 to March 31, 2022.

*Consumer confidence for the 12 months at a given point in time. E.g., the figure at March 2021 was how confident people were at that time about the next 12 months. The March 2022 figure was how confident people were last month about the year ahead. †Consumer confidence balance scale from 100 (extreme confidence) to -100 (extreme lack of confidence). Sources: European Commission, S&P Global/Haver Analytics.

The affected food and energy categories make up 36% of the eurozone inflation basket. In other words, prices of 36% of the average consumption basket have been rising and will likely continue to do so, reducing consumers’ ability to spend on other items (Figure 1). Wages in the currency bloc tend to adjust slowly to inflation, and the rapidity of the recent inflation surge following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means that consumers will have less cash in the pocket to spend on goods and services.

Survey evidence for March shows that consumers are already significantly concerned about their finances. Eurozone consumer expectations of finances over the next 12 months—traditionally a strong indicator of household consumption—have deteriorated sharply. In the 2008 and 2011 recessions, this indicator also fell shortly before the manufacturing PMI, which fell in March but remains significantly above recession territory (Figure 2). Overall, survey indicators suggest that private consumption in the eurozone will weaken significantly this year.

...survey indicators suggest that private consumption in the eurozone will weaken significantly...

Will weaker consumption turn into a Europe‑wide economic recession? There are five important mitigating factors to consider.

First, in contrast to previous episodes of rapid inflation, many European governments are using fiscal policy to partially offset the effects on consumers. Before the war in Ukraine began, Italy had already spent 1% of its GDP to shield households and small businesses from the rapid rise in gas prices that started in 2021; Germany is spending EUR 15 billion (0.4% of GDP) to lower petrol pump prices to prewar levels between April and June; Spain has announced a 1.5% of GDP package to achieve the same outcome. These fiscal subsidies will mean that disposable incomes face less strain from higher inflation, thereby reducing the drag on consumer demand.

Second, there will be an increase in war‑related government spending. The arrival of 4 million Ukrainian refugees in the eurozone will likely raise private consumption by 0.5% to 1% this year via the subsistence payments, access to schooling and health facilities, and social benefits that European governments will provide.

Third, European governments have hiked defense spending in response to the onset of the war, most notably Germany, which has pledged a EUR 100 billion package to modernize its armed forces. There will also be a rise in spending to make economies independent of Russian gas as quickly as feasible, including the construction of liquid natural gas terminals across several countries—but these projects will likely take time to have a meaningful effect on growth.

Fourth, the removal of all COVID‑19 restrictions will support a rebound in services activity in the short term. There was a rise in excess savings in the eurozone during the COVID‑19 lockdowns—however, these savings are very unevenly distributed, which means that this factor will only have a small mitigating effect for households in the bottom 50% of income distribution.

Finally, German manufacturing order books remain at their highest level since data began in the 1960s. Supply chains had begun to improve before the war, and recent data clearly show a rapid rise in industrial production and export performance as German factories have begun to work through the backlog. Although the war has disrupted supply chains between Ukraine and Western Europe, alternative supply chains should be established over the course of the year.

Taken together, these mitigating factors suggest that the eurozone has at least a chance of avoiding recession. As things stand, we believe the current probability of a eurozone recession is around 50% this year. There are several scenarios that would make a recession more likely: (1) a gas shortage from Russia, whether due to embargo or gas weaponization; (2) a persistent rise in oil prices to levels of USD 25 per barrel in the second and third quarters; (3) a widespread COVID‑19‑induced lockdown in China, which would adversely affect external demand and supply. On the other hand, a rapid de‑escalation in the Russia‑Ukraine conflict, leading to a 25% to 30% decline in oil and gas prices, will make a recession much less likely.

The war in Ukraine has made life more difficult for the ECB. Along with the other leading central banks, the ECB was widely expected to tighten monetary policy this year as the global economy recovered from the COVID‑19 shock. However, as well as aggravating inflationary pressures, the war in Ukraine is likely to lower growth as a result of much higher energy and food prices. Tightening monetary policy is a much riskier move during periods of low growth.

The war in Ukraine has made life more difficult for the ECB.

At its March meeting, the ECB reduced the pace of quantitative easing (QE) purchases and indicated that it may end them completely by the end of September. At the same time, it changed the guidance to say that the adjustment in rates will take place “some time” rather than “shortly” after the end of QE. The ECB also stressed that changes to both policies will be data dependent, and will particularly depend on the evolution of the medium‑term inflation outlook.

Despite the large shocks the bloc faces, the ECB still expects growth of 3.7% in its base‑case scenario. However, I believe this is unrealistic and that growth of around 2% is more likely. Such a large revision in the ECB’s growth forecast could lead to a longer period of asset purchases and push back the timing of interest rate hikes, relative to current market pricing.

Financial markets have currently priced in four ECB rate hikes within a year. Our real economy view suggests that this is too ambitious. Given recent inflation surprises and the deteriorating real economic outlook, we believe the ECB will exit QE in July and raise rates in September. It will then likely be able to hike once or twice more before inflation declines and a weakening economy mean it has to pause again.

While bund yields remain at historically very low levels, a change in ECB policy, especially with respect to QE, could still lead to a rally in bund yields—indeed, the prospect of a recession has historically led to an inverted bund yield curve. However, bund yields are roughly 100 basis points above the policy rate and 45 basis points above the two‑year rate. This suggests that there is still significant room for the bund yield curve to flatten despite the historic highs in valuations.

1Actual future outcomes may differ materially from any estimates or forward-looking statements made.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.